Antony Blinken

Antony Blinken | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 2021 | |

| 71st United States Secretary of State | |

| Assumed office January 26, 2021 | |

| President | Joe Biden |

| Deputy | Wendy Sherman Victoria Nuland (acting) Kurt M. Campbell |

| Preceded by | Mike Pompeo |

| 18th United States Deputy Secretary of State | |

| In office January 9, 2015 – January 20, 2017 | |

| President | Barack Obama |

| Preceded by | William J. Burns |

| Succeeded by | John Sullivan |

| 26th United States Deputy National Security Advisor | |

| In office January 20, 2013 – January 9, 2015 | |

| President | Barack Obama |

| Leader | Susan Rice |

| Preceded by | Denis McDonough |

| Succeeded by | Avril Haines |

| National Security Advisor to the Vice President of the United States | |

| In office January 20, 2009 – January 20, 2013 | |

| Vice President | Joe Biden |

| Preceded by | John P. Hannah |

| Succeeded by | Jake Sullivan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Antony John Blinken April 16, 1962 Yonkers, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2 |

| Parent |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Education | |

Antony John Blinken (born April 16, 1962) is an American lawyer and diplomat currently serving as the 71st United States secretary of state. He previously served as deputy national security advisor from 2013 to 2015 and deputy secretary of state from 2015 to 2017 under President Barack Obama.[1] Blinken was previously national security advisor to then-Vice President Joe Biden from 2009 to 2013.

During the Clinton administration, Blinken served in the State Department and in senior positions on the National Security Council from 1994 to 2001. He was a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies from 2001 to 2002. He advocated for the 2003 invasion of Iraq while serving as the Democratic staff director of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee from 2002 to 2008.[2] He was a foreign policy advisor for Joe Biden's 2008 presidential campaign, before advising the Obama–Biden presidential transition.

From 2009 to 2013, Blinken served as deputy assistant to the president and national security advisor to the vice president. During his tenure in the Obama administration, he helped craft U.S. policy on Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the nuclear program of Iran.[3][4] After leaving government service, Blinken moved into the private sector, co-founding WestExec Advisors, a consulting firm. Blinken returned to government first as a foreign policy advisor for Biden's 2020 presidential campaign, then as Biden's pick for secretary of state, a position the Senate confirmed him for on January 26, 2021.

Early life and education

Blinken was born on April 16, 1962, in Yonkers, New York, to Jewish parents. His mother was Judith (née Frehm) Blinken and his father was Donald M. Blinken, who later served as the U.S. ambassador to Hungary.[5][6][7] His maternal grandparents were Hungarian Jews.[8] Blinken's uncle, Alan Blinken, served as the U.S. ambassador to Belgium.[9][10] His paternal grandfather, Maurice Henry Blinken, was an early backer of Israel who studied its economic viability,[11] and his great-grandfather was Meir Blinken, a Yiddish writer.[12]

Blinken attended the Dalton School in New York City until 1971.[6] He then moved to Paris with his mother and Samuel Pisar; his mother married Pisar after divorcing Donald Blinken. In his confirmation hearing, Blinken recalled the story of his stepfather, Pisar, who had been the only Holocaust survivor of the 900 children in his school in Poland. Pisar found refuge in a U.S. tank after making a break into the forest during a Nazi death march.[13][14] In Paris, Blinken attended École Jeannine Manuel.[15]

From 1980 to 1984, Blinken attended Harvard University, where he majored in social studies. He co-edited Harvard's daily student newspaper, The Harvard Crimson,[5][16][17] and wrote a number of articles on current affairs.[18][19] After graduating from the university, Blinken worked as an intern for The New Republic for about a year.[6][19] He earned a J.D. from Columbia Law School in 1988[20][21] and practiced law in New York City and Paris.[22] Blinken worked with his father to raise funds for Michael Dukakis, the Democratic nominee in the 1988 United States presidential election.[5]

In his monograph Ally versus Ally: America, Europe, and the Siberian Pipeline Crisis (1987), Blinken argued that exerting diplomatic pressure on the Soviet Union during the Siberian pipeline crisis was less significant for American interests than maintaining strong relations between the United States and Europe.[23] Ally versus Ally was based on Blinken's undergraduate thesis in which he interviewed Henry Kissinger.[16][24]

Early career

Clinton and Bush administrations

Blinken has held senior foreign policy positions in two administrations over two decades.[5] He was a member of the National Security Council (NSC) staff from 1994 to 2001.[25] From 1994 to 1998, Blinken was special assistant to the president and senior director for strategic planning and NSC senior director for speechwriting.[26] From 1999 to 2001, he was special assistant to the president and senior director for European and Canadian affairs.[27]

Blinken supported the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003.[2][28] In 2002, he was appointed staff director for the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, a position he served in until 2008.[25] Blinken assisted then-Senator Joe Biden, Chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, in formulating Biden's support for the U.S. invasion of Iraq, with Blinken characterizing the vote to invade Iraq as "a vote for tough diplomacy".[29]

In the years following the U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq, Blinken assisted Biden in formulating a proposal in the Senate to establish in Iraq three independent regions divided along ethnic or sectarian lines: a "Shiastan" in the south, a "Sunnistan" in the north, as well as Iraqi Kurdistan. The proposal was overwhelmingly rejected at home, as well as in Iraq, where the prime minister opposed the partition plan.[30]

He was also a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. In 2008, Blinken worked for Joe Biden's presidential campaign,[5] and was a member of the Obama–Biden presidential transition team.[31]

Obama administration

From 2009 to 2013, Blinken was Deputy Assistant to the President and National Security Advisor to the Vice President. In this position he helped craft U.S. policy on Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the nuclear program of Iran.[3][4] Blinken was sworn in as deputy national security advisor, succeeding Denis McDonough, on January 20, 2013.[32]

On November 7, 2014, President Obama announced that he would nominate Blinken for the Deputy Secretary post, replacing the retiring William J. Burns.[33] On December 16, 2014, Blinken was confirmed as Deputy Secretary of State by the Senate by a vote of 55 to 38.[34]

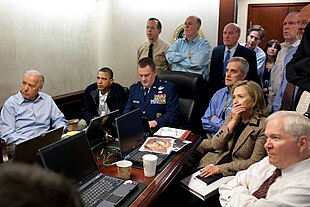

Of Obama's 2011 decision to kill Osama bin Laden, Blinken said "I've never seen a more courageous decision made by a leader."[35] A 2013 profile described him as "one of the government's key players in drafting Syria policy",[5] for which he served as a public face.[36] Blinken was influential in formulating the Obama administration's response to the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation in the aftermath of the 2014 Ukrainian revolution.[37][38]

Blinken supported the 2011 military intervention in Libya[36] and the supply of weapons to Syrian rebels.[39] He condemned the 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt and expressed support for the democratically elected Turkish government and its institutions, but also criticized the 2016–present purges in Turkey.[40] In April 2015, Blinken voiced support for the Saudi Arabian–led intervention in Yemen.[41] He said that "as part of that effort, we have expedited weapons deliveries, we have increased our intelligence sharing, and we have established a joint coordination planning cell in the Saudi operation centre."[42]

Blinken worked with Biden on requests for American money to replenish Israel's arsenal of Iron Dome interceptor missiles during the 2014 Israel–Gaza conflict.[43] In May 2015, Blinken criticized the persecution of Muslims in Myanmar and warned Myanmar's leaders about the dangers of anti-Muslim legislation,[44] saying that Rohingya Muslims "should have a path to citizenship. The uncertainty that comes from not having any status is one of the things that may drive people to leave."[45]

In June 2015, Blinken claimed that more than ten thousand ISIL fighters had been killed by American-led airstrikes against the Islamic State since a U.S.-led coalition launched a campaign against it nine months previously.[46]

Penn Biden Center

From 2017 to 2019, Blinken served as the managing director of the Penn Biden Center, a University of Pennsylvania think tank based in Washington.[47] During this time he published several articles on foreign policy and the Trump administration.

Secretary of state

Nomination and confirmation

.jpg/220px-Secretary_Blinken_is_Sworn_in_as_Secretary_of_State_(50878397918).jpg)

Blinken was a foreign policy advisor for Biden's 2020 presidential campaign.[48] On November 22, 2020, Bloomberg News reported that Biden had selected Blinken as his nominee for secretary of state.[49] These reports were later corroborated by The New York Times and other outlets.[30][50][49] On November 24, upon being announced as Biden's choice for secretary of state, Blinken said, "We can't solve all the world's problems alone [and] we need to be working with other countries."[51] He had earlier remarked in a September 2020 interview with the Associated Press that "democracy is in retreat around the world, and unfortunately it's also in retreat at home because of the president taking a two-by-four to its institutions, its values and its people every day."[52]

Blinken's confirmation hearing before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee began on January 19, 2021. His nomination was confirmed by the committee on January 25 with a vote of 15–3.[53] On January 26, Blinken was confirmed in the full Senate by a vote of 78–22.[1] Blinken took the oath of office of the secretary of state later that day.[54] In doing so, he became the third former deputy secretary of state to serve as the Secretary of State, after Lawrence Eagleburger and Warren Christopher in 1992 and 1993, respectively.[55][56]

Tenure

Myanmar

On January 31, 2021, Blinken condemned the 2021 Myanmar coup d'état and expressed grave concerns on the detention of government officials and civil society leaders, calling for their immediate release.[57] He stated that, "the United States will continue to take firm action against those who perpetrate violence against the people of Burma as they demand the restoration of their democratically elected government."[58]

Afghanistan

In February 2021, having spoken to president Ashraf Ghani, Blinken voiced support for Afghan peace negotiations with Taliban Islamist rebels and reiterated the United States' commitment to a peace deal that includes a "just and durable political settlement and permanent and comprehensive ceasefire."[59]

.jpg/220px-Secretary_Blinken_Meets_with_Afghan_President_Ghani_(51126100940).jpg)

Blinken made an unannounced visit to Kabul on April 15 and met with U.S. military and diplomatic personnel following the Biden administration's announcement of the 2021 withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan.[60] He said the decision to withdraw from Afghanistan was made to focus resources on China and the COVID-19 pandemic.[61] He faced calls to resign as secretary of state following the US withdrawal from Afghanistan.[62][63][64][65]

In August 2021, Blinken rejected comparisons between the deteriorating situation in Afghanistan due to the Taliban offensive, which started in May 2021 after U.S. and coalition military forces began withdrawing from Afghanistan, and the chaotic American departure from Saigon in 1975, saying that "We went to Afghanistan 20 years ago with one mission, and that mission was to deal with the folks who attacked us on 9/11 and we have succeeded in that mission."[66]

Africa

.jpg/220px-Secretary_Blinken_Meets_With_Kenyan_President_Ruto_(52375711450).jpg)

In February 2021, Blinken condemned ethnic cleansing in the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia and called for the immediate withdrawal of Eritrean forces and other fighters.[67][68]

In the midst of the Biden administration's continuing review of the normalization agreement between Morocco and Israel enacted during the previous administration, Blinken maintained that the recognition of Morocco's sovereignty over the disputed territory of Western Sahara, which was annexed by Morocco in 1975, will not be reversed imminently. During internal discussions, he supported improving relations between the two countries and expressed urgency in appointing a United Nations envoy to Western Sahara.[69][70]

In March 2023, he met with Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed in Addis Ababa to normalize relations between the United States and Ethiopia that were strained by the Tigray War between the Ethiopian government and Tigray rebels.[71]

South America

Blinken spoke with the interim president of Venezuela, Juan Guaidó, whom the Biden administration will continue to recognize as the country's head of state and not Nicolás Maduro.[72]

Asia

.jpg/220px-Tony_Blinken_and_Bongbong_Marcos_shaking_hands_2_(2022-08-06).jpg)

Blinken made his first international trip with Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin to Tokyo and Seoul on March 15, during which he warned China against coercion and aggression.[73][74] He also condemned the Chinese government for committing genocide against ethnic Uyghurs.[75]

In July 2021, the Biden administration accused China of a global cyberespionage campaign, which Blinken said posed "a major threat to our economic and national security".[76]

In late April 2021, Blinken denounced the sentencing of Hong Kong pro-democracy activists Jimmy Lai, Albert Ho, and Lee Cheuk-yan among others, for their roles in the 2019 Hong Kong protests, calling it a "politically-motivated" decision.[77][78]

In May 2022, Blinken stated that "China is the one country that has the intention as well as the economic, technological, military and diplomatic means to advance a different vision of international order."[79] He dismissed China's claims to be neutral in the Russo-Ukrainian War and accused China of supporting Russia.[80]

In June 2023, Blinken met with Chinese President Xi Jinping during his trip to Beijing. According to the State Department's readout, Blinken "emphasized the importance of maintaining open channels of communication across the full range of issues to reduce the risk of miscalculation" and "made clear that while we will compete vigorously, the United States will responsibly manage that competition so that the relationship does not veer into conflict."[81]

G7 meeting

.jpg/220px-Secretary_Blinken_Meets_with_Chinese_State_Councilor_and_Foreign_Minister_Wang_Yi_in_Bali_(52204013285).jpg)

In May 2021, Blinken traveled to London and Reykjavík for the G7 Foreign and Development Ministers' meeting and the Arctic Council Ministerial meeting respectively.[82][83] In a meeting with president Volodymyr Zelensky and foreign minister Dmytro Kuleba in Kyiv, Blinken reaffirmed support for Ukraine's sovereignty and territorial integrity against "Russian aggression".[84] During the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Blinken expressed support for Israel's right to defend itself but warned that evicting Palestinian families from their homes in East Jerusalem is among the actions that could further escalate outbreaks of violence and retaliation.[85][86] He, along with the United Nations Security Council, called for full adherence to the truce and stressed the immediate need for humanitarian aid for Palestinian civilians while reiterating the need for a two-state solution.[87] Following the ceasefire and coinciding Blinken's visit to Jerusalem on May 25, the transfer of food and medical supplies furnished by the United Nations and Physicians for Human Rights, aid workers, and journalists were permitted into the Gaza Strip.[88]

Europe

.jpg/220px-210414-D-XI929-1005_(51115721097).jpg)

The decision to waive sanctions against Nord Stream AG and its chief executive Matthias Warnig, subsequent to the completion of the Nord Stream 2 natural gas pipeline, drew congressional criticisms.[89] Blinken defended the action as pragmatic and practical to U.S. interests and remarked that proceeding otherwise would be counterproductive with European relations.[89] In June 2021, Blinken traveled with Biden to attend the 47th G7 summit in Cornwall, the 31st NATO summit in Brussels, and the summit meeting with president Vladimir Putin in Geneva.[90] Blinken and Biden both acknowledged that relations between the U.S. and Russia were at their lowest point, and a more predictable relationship remained a key priority.[91] However, he signaled that further punitive actions would be enforced if the Russian government chose to continue with hostile activities such as interference in the 2020 presidential elections, the SolarWinds cyberattack, or the apparent poisoning and imprisonment of Alexei Navalny.[91] Of the administration's decision to forgo a joint press conference after the summit, Blinken explained that it was "the most effective way" and "not a rare practice".[92]

Later that month, Blinken traveled to Brussels for a NATO Ministerial with European Union counterparts to underscore the Biden administration's determination to strengthen transatlantic alliances.

Blinken has been a co-chair of the Trade and Technology Council since its creation in 2021 to encourage trade relations with the European Union.[93]

Russia-Ukraine war

In January 2022, Blinken authorized the supply of weapons to Ukraine to support the Eastern European country in amid border tensions with Russia.[94][95] At a joint press availability with Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba on January 19, Blinken said "One of the principles which you've heard us repeat – but it always bears repeating – is nothing about Ukraine without Ukraine.[96] Blinken publicly warned on February 11 of the likelihood of a Russian invasion of Ukraine prior to the end the 2022 Winter Olympics[97] and on February 13, he said the risk was "high enough and the threat is imminent enough" that the evacuation of most staff from the U.S. Embassy in Kyiv was "the prudent thing to do".[98] In September 2022, Blinken pledged that the United States would help the Ukrainian military retake Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine.[99] He criticized Vladimir Putin's threats to use nuclear weapons, saying that "Russia has gotten itself into the mess that it's in is because there is no one in the [autocratic] system to effectively tell Putin he's doing the wrong thing."[100]

Regarding the countries that decided to be neutral in the war between Russia and Ukraine, Blinken said that "It's pretty hard to be neutral when it comes to this aggression. There is a clear aggressor. There is a clear victim."[101]

Speaking about the 2022 Russian mobilization, he said that mobilized Russian civilians were being treated as "cannon fodder that Putin is trying to throw into the war."[102] On October 21, 2022, Blinken said the United States saw no willingness on the side of Russia to end its war in Ukraine by diplomatic means, despite American attempts.[103] Blinken questioned China's peace proposal, saying "the world should not be fooled by any tactical move by Russia, supported by China or any other country, to freeze the war on its own terms."[104] In June 2023, he rejected any "cease-fire that simply freezes current lines in place".[105] In July 2023, he defended Biden's decision to supply Ukraine with cluster munitions.[106]

Americans detained abroad

Blinken and the Biden administration have been criticized for the handling of Americans who are wrongfully imprisoned abroad. Families of U.S. detainees in the Middle East were upset that they were left off of a call with Secretary Blinken.[107] In July 2022, Blinken had a meeting with Sergey Lavrov to discuss a prisoner swap to secure the release of Paul Whelan and Brittney Griner.[108] Blinken has met with the Bring Our Families Home campaign, a coalition of families with loved ones detained abroad.[109]

Blinken, along with the work of Special Presidential Envoy of Hostage Affairs Roger D. Carstens, has negotiated the release of over a dozen Americans wrongfully detained or held hostage abroad including Trevor Reed, Danny Fenster, Baquer Namazi, the entire Citgo Six, Osman Khan, Matthew John Heath, Mark Frerichs, and Jorge Alberto Fernández.

Foreign policy positions

.jpg/220px-Deputy_Secretary_Blinken_Meets_With_National_League_for_Democracy_Leader_Daw_Aung_San_Suu_Kyi_in_Naypyitaw_(24402014001).jpg)

As foreign policy advisor to then 2020 Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden, The New York Times described Blinken as "ha[ving] Biden's ear on policy issues".[110] His foreign policy positions have been described as hawkish.[111] Blinken has asserted that "[Biden] would not tie military assistance to Israel to things like annexation or other decisions by the Israeli government with which we might disagree".[112] Blinken praised the Trump administration-brokered normalization agreements between Israel and Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates.[113][114] On October 28, 2020, Blinken reaffirmed that a Biden administration will undertake strategic review of the relationship between the United States and Saudi Arabia, ensuring that it advances U.S interests and values.[115] In January 2021, Blinken has stated the Biden administration would keep the American embassy to Israel in Jerusalem and would seek a two-state solution to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[116]

Blinken is in favor of continuing non-nuclear sanctions against Iran and described it as "a strong hedge against Iranian misbehavior in other areas".[113] He criticized former president Trump's withdrawal of the U.S. from the international nuclear agreement with Iran and expressed support for a "longer and stronger" nuclear deal.[117][118] Blinken did not rule out a military intervention to stop Iran from obtaining nuclear weapons.[119][120]

Blinken has been critical of the Trump administration in aiding China to advance its own key strategic goals. He stated: "[Trump] weaken[ed] American alliances, leaving a vacuum in the world for China to fill, abandoning our values and giving China a green light to trample on human rights and democracy from Xinjiang to Hong Kong".[121] However, he also credited the former president's administration for its aggressive approach and has characterized China as a "techno-autocracy" which seeks world dominance.[122][123] He indicated a desire to welcome political refugees from Hong Kong and stated that the Biden administration's commitment to Taiwan's defense would "absolutely endure", and that China's use of military force against Taiwan "would be a grievous mistake on their part".[123] Blinken has also viewed China is committing genocide and crimes against humanity against Uyghur Muslims and other ethnic minorities in its northwestern region of Xinjiang.[124] Blinken has characterized former president Trump's Phase One trade deal with China as "a debacle".[125] He said it was unrealistic to "fully decouple" from China and has expressed support for "stronger economic ties with Taiwan".[125][126]

Blinken has indicated American interest in robust ties between itself, Greece, Israel, and Cyprus regarding the Eastern Mediterranean Security and Energy Partnership Act and acknowledged the threats posed by an expansionist Turkey, which is "not acting like an ally".[127] He opposed Turkish president Recep Erdogan's call for "a two-state solution in Cyprus", saying the Biden administration is committed to the reunification of Cyprus.[40][128] Blinken has also suggested that he would consider sanctioning the Erdogan administration.[129] Blinken reaffirmed his support of keeping NATO's door open for Georgia, a country in the Caucasus, and raised the argument that NATO member countries have been more effectively shielded from "Russian aggression".[130]

Blinken expressed his support of extending the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty with Russia to limit the number of deployed strategic nuclear warheads.[30][131] Blinken said the Biden administration will "review" security assistance to Azerbaijan due to the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war between Azerbaijan and Armenia over the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh and voiced his support for "the provision to Armenia of security assistance".[132]

.jpg/220px-Secretary_Blinken_Meets_with_Israeli_Prime_Minister_(53453696214).jpg)

Blinken opposed the United Kingdom's separation from the European Union and referred to it as a "total mess" with consequences adverse to U.S. interest.[133][134] Blinken expressed concern over perceived human rights violations in Egypt under the presidency of Abdel Fattah el-Sisi.[135] He condemned the arrest of three employees for the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights organization, saying that "meeting with foreign diplomats is not a crime. Nor is peacefully advocating for human rights."[136] Referring to the re-instated Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, declared by the Taliban following their 2021 capture of Kabul, Blinken has stated that the United States will not recognize any government that harbors terrorist groups or that does not uphold basic human rights.[137]

During a visit to Tel Aviv following the Hamas attack on Israel, Blinken promised to help defend Israel "as long as America exists." Blinken said that "Israel has the right, indeed the obligation, to defend itself and to ensure that this never happens again."[138] He rejected calls for a ceasefire in the Israel–Hamas war but said he supported "humanitarian pauses" to deliver aid to the people of the Gaza Strip.[139] Supporters of the Palestinian cause established an encampment outside Blinken's home in McLean, Virginia, named 'Kibbutz Blinken.'[140]

Personal life

.jpg/220px-Secretary_Blinken_performs_during_the_Global_Music_Diplomacy_Initiative_Launch_(53220710805).jpg)

Blinken is Jewish.[141] In 2002, Blinken and Evan Ryan were married in an interfaith ceremony officiated by a rabbi and a priest at Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Washington, D.C.[20][5] They have two children.[142] Blinken is fluent in French.[143] He plays the guitar and has three songs available on Spotify by the alias Ablinken[144] (pronounced "Abe Lincoln").[145] Blinken gave a cover performance of "Hoochie Coochie Man" by Muddy Waters in September 2023 to launch the Global Music Diplomacy Initiative at the State Department, the video of which went viral.[146][147][148][149]

Private sector

WestExec Advisors

In 2017, Blinken co-founded WestExec Advisors, a political strategy advising firm, with Michèle Flournoy, Sergio Aguirre, and Nitin Chadda.[150][151] WestExec's clients have included Google's Jigsaw, Israeli artificial-intelligence company Windward, surveillance drone manufacturer Shield AI, which signed a $7.2 million contract with the Air Force,[152] and "Fortune 100 types".[153] According to Foreign Policy, the firm's clientele includes "the defense industry, private equity firms, and hedge funds".[154] Blinken received almost $1.2 million in compensation from WestExec.[155]

In an interview with The Intercept, Flournoy described WestExec's role as facilitating relationships between Silicon Valley firms and the Department of Defense and law enforcement;[156] Flournoy and others compared WestExec to Kissinger Associates.[156][157]

Pine Island Capital Partners

Blinken, as well as other Biden transition team members Michele Flournoy, former Pentagon advisor, and Lloyd Austin, Secretary of Defense, are partners of private equity firm Pine Island Capital Partners,[158][159] a strategic partner of WestExec.[160] Pine Island's chairman is John Thain, the final chairman of Merrill Lynch before its sale to Bank of America.[161] Blinken went on leave from Pine Island in August 2020 to join the Biden campaign as a senior foreign policy advisor.[159] He said he would divest himself of his equity stake in Pine Island if confirmed for a position in the Biden administration.[160]

During the final stretch of Biden's presidential campaign, Pine Island raised $218 million for a special-purpose acquisition company (SPAC), a public offering to invest in "defense, government service and aerospace industries" and COVID-19 relief, which the firm's prospectus (initially filed with the U.S. SEC in September and finalized on November 13, 2020) predicted would be profitable as the government looked to private contractors to address the pandemic.[159] Thain said he chose the other partners because of their "access, network and expertise".[152]

In a December 2020 New York Times article raising questions about potential conflicts of interest between WestExec principals, Pine Island advisors, including Blinken, and service in the Biden administration, critics called for full disclosure of all WestExec/Pine Island financial relationships, divestiture of ownership stakes in companies bidding on government contracts or enjoying existing contracts, and assurances that Blinken and others recuse themselves from decisions that might advantage their previous clients.[152]

Blinken is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations[162] and was previously a global affairs analyst for CNN.[163][164]

Publications

- Blinken, Antony J. (1987). Ally versus Ally: America, Europe, and the Siberian Pipeline Crisis. New York: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-92410-6. OCLC 14359172.[5]

- Blinken, Antony J. (2001). "The False Crisis Over the Atlantic". Foreign Affairs. 80 (3): 35–48. doi:10.2307/20050149. JSTOR 20050149.

- Blinken, Antony J. (June 2002). "Winning the War of Ideas". The Washington Quarterly. 25 (2): 101–114. doi:10.1162/01636600252820162. ISSN 0163-660X. S2CID 154183240.

- Blinken, Antony J. (December 2003). "From Preemption to Engagement". Survival. 45 (4): 33–60. doi:10.1080/00396330312331343576. ISSN 0039-6338. S2CID 154077314.

See also

References

- ^ a b "Senate confirms Antony Blinken as 71st secretary of state". AP NEWS. January 26, 2021. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ a b Glueck, Katie; Kaplan, Thomas (January 12, 2020). "Joe Biden's Vote for War". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 18, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ a b "Senate Confirms Antony "Tony" Blinken '88 as Secretary of State". Columbia Law School. December 17, 2014. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ a b Sanger, David E. (November 7, 2014). "Obama Makes His Choice for No. 2 Post at State Department". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 20, 2015. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Horowitz, Jason (September 20, 2013). "Antony Blinken steps into the spotlight with Obama administration role". The Washington Post. p. C1. ProQuest 1432540846. Archived from the original on September 16, 2013. Retrieved September 28, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Antony 'Tony' Blinken". Jewish Virtual Library. 2013. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- ^ "Frehm – Blinken". The New York Times. December 7, 1957. Archived from the original on March 24, 2017. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Andriotakis, Pamela (August 25, 1980). "Sam and Judith Pisar Meld the Disparate Worlds of Cage and Kissinger in Their Marriage". People. Archived from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Russell, Betsy Z. (November 23, 2020). "Why Biden's pick for Secretary of State has a name that's familiar in Idaho politics ..." Idaho Press. Archived from the original on November 29, 2020. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ Finnegan, Conor (November 24, 2020). "Who is Tony Blinken? Biden taps close confidante, longtime aide for secretary of state". ABC News. Archived from the original on December 2, 2020. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ "Maurice Blinken, 86; Early Backer of Israel". The New York Times. July 15, 1986. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 30, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Briman, Shimon (November 30, 2020). "Yiddish and the Ukrainian–Jewish roots of the new U.S. Secretary of State". Translated by Marta D. Olynyk. Ukrainian Jewish Encounter. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ Wisse, Ruth R. (February 2021). "A Tale of Five Blinkens". Commentary. Archived from the original on January 19, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Statement for the Record Archived March 4, 2021, at the Wayback Machine before the United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Antony J. Blinken, Nominee for Secretary of State, January 19, 2021.

- ^ Bezioua, Céline. "Venue d'Antony Blinken à l'école" (in French). École Jeannine Manuel. Archived from the original on April 20, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ a b Uribe, Raquel Coronell; Griffin, Kelsey J. (December 7, 2020). "President-elect Joe Biden Nominates Harvard Affiliates to Top Executive Positions". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ "Anthony J. Blinken". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on December 10, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2020.

- ^ Paumgarten, Nick (December 7, 2020). "A Dad-Rocker in the State Department". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ^ a b Rodríguez, Jesús (January 11, 2021). "The World According to Tony Blinken – in the 1980s". Politico. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ a b "WEDDINGS; Evan Ryan, Antony Blinken". The New York Times. March 3, 2002. Archived from the original on December 7, 2013. Retrieved September 28, 2013.

- ^ "Deputy Secretary of State Antony Blinken '88 Speaks at Annual D.C. Alumni Dinner". Columbia Law School. April 30, 2015. Archived from the original on September 18, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Sorcher, Sara (July 17, 2013). "Antony Blinken, Deputy National Security Adviser". National Journal. Archived from the original on February 14, 2015.

- ^ Miller, Chris (December 3, 2020). "The Ghost of Blinken Past". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on December 6, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ Guyer, Jonathan (June 8, 2023). "I Crashed Henry Kissinger's 100th-Birthday Party". Intelligencer. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Gaouette, Nicole; Hansler, Jennifer; Atwood, Kylie (November 24, 2020). "Biden picks loyal lieutenant to lead mission to restore US reputation on world stage". CNN. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ "Antony J. Blinken". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ Gallucci, Robert (2009). Instruments and Institutions of American Purpose. United States: Aspen Institute. p. 112. ISBN 9780898435016. Archived from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- ^ Fordham, Evie (November 23, 2020). "Biden secretary of state pick Blinken criticized over Iraq War, consulting work". Fox News. Archived from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Johnson, Jake (November 27, 2020). "As Biden taps Blinken as Secretary of State, critics denounce support for invasions of Iraq, Libya". Salon. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c Jakes, Lara; Crowley, Michael; Sanger, David E. (November 23, 2020). "Biden Chooses Antony Blinken, Defender of Global Alliances, as Secretary of State". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ LaMonica, Gabe (December 17, 2014). "Blinken confirmed by Senate as Kerry's deputy at State". CNN. Archived from the original on February 20, 2015. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

- ^ Nakamura, David; Horwitz, Sari (January 25, 2013). "Obama taps McDonough as chief of staff, says goodbye to longtime adviser Plouffe". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ^ "Obama nominates his adviser Tony Blinken as Deputy Secretary of State". Reuters. Archived from the original on November 8, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 113th Congress – 2nd Session". senate.gov. Archived from the original on September 25, 2018. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^ Mann, Jim (2012). The Obamians: The Struggle Inside the White House to Redefine American Power. New York: Viking Press. p. 313. ISBN 9780670023769. OCLC 1150993166.

- ^ a b Allen, Jonathan (September 16, 2013). "Tony Blinken's star turn". Politico. Archived from the original on August 28, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Gramer, Robbie; Detsch, Jack (November 23, 2020). "Biden's Secretary of State Pick Bodes Return to Normalcy for Weary Diplomats". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Zeleny, Jeff; Merica, Dan; Atwood, Kylie (November 22, 2020). "Biden poised to nominate Antony Blinken as secretary of state". CNN. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ "W.H. defends plan to arm Syrian rebels". CNN. September 18, 2014. Archived from the original on October 19, 2017. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ a b "ABD yönetimine Türkiye açısından kritik isimler". Deutsche Welle (in Turkish). November 23, 2020. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ "Yemen conflict: US boosts arms supplies for Saudi-led coalition". BBC News. April 7, 2015. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ "US steps up arms for Saudi campaign in Yemen". Al Jazeera. April 8, 2015. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Magid, Jacob (November 24, 2020). "In tapping Blinken, Biden will be served by confidant with deep Jewish roots". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on November 30, 2020. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- ^ "Myanmar population control bill signed into law despite concerns it could be used to persecute minorities". ABC News. May 24, 2015. Archived from the original on March 12, 2018. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ "Myanmar should share responsibility for Rohingya crisis: US". Business Standard. May 23, 2015. Archived from the original on October 19, 2016. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ Mroue, Bassem (June 3, 2015). "U.S. official: Airstrikes killed 10,000 Islamic State fighters". USA Today. Archived from the original on December 6, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ Associated Press (January 29, 2023). "Classified docs probe pushes Biden think tank into spotlight". AP News. Retrieved September 1, 2023.

- ^ Hook, Janet; Wilkinson, Tracy (November 23, 2020). "Biden's longtime advisor Antony Blinken emerges as his pick for secretary of State". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 2, 2020. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- ^ a b Pager, Tyler; Epstein, Jennifer; Mohsin, Saleha (November 22, 2020). "Biden to Name Longtime Aide Blinken as Secretary of State". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved November 22, 2020.

- ^ Herszenhorn, David M.; Momtaz, Rym (November 23, 2020). "9 things to know about Antony Blinken, the next US secretary of state". Politico. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- ^ Smith, David (November 24, 2020). "'A cabinet that looks like America': Harris hails Biden's diverse picks". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- ^ Lee, Matthew (November 22, 2020). "Biden expected to nominate Blinken as secretary of state". AP News. Archived from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- ^ Zengerle, Patricia; Pamuk, Humeyra (January 26, 2021). "U.S. Senate expected to confirm Blinken as Secretary of State on Tuesday". Reuters. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ Hansler, Jennifer (January 26, 2021). "Antony Blinken sworn in as Biden's secretary of state". CNN. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ "Biographies of the Secretaries of State: Warren Minor Christopher (1925–2011)". U.S. Department of State. n.d. Archived from the original on December 5, 2018. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ "Biographies of the Secretaries of State: Lawrence Sidney Eagleburger (1930–2011)". U.S. Department of State. n.d. Archived from the original on December 5, 2018. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ "Top U.S. diplomat Blinken calls on Myanmar military leaders to release Suu Kyi, others". Reuters. February 1, 2021. Archived from the original on February 8, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ "U.S.'s Blinken vows 'firm action' against Myanmar military". Reuters. February 4, 2021. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ "Blinken tells Ghani U.S. supports Afghanistan peace process – statement". Reuters. February 18, 2021. Archived from the original on March 18, 2021. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ Hansler, Jennifer (April 15, 2021). "Secretary of State Blinken visits Afghanistan day after US announces plans for withdrawal". CNN. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Focus Shifting to China From Afghanistan, Blinken Says". Bloomberg. April 18, 202. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021.

- ^ "Secretary of State Antony Blinken needs to resign". New York Post. August 20, 2021. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ "Blinken must resign". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ Chasmar, Jessica (September 13, 2021). "Multiple GOP congressmen tell Blinken to resign during heated Afghanistan hearing". Fox News. Archived from the original on April 14, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ ""Fatally Flawed": GOP congressman tells Blinken to resign as Afghanistan hearing heats up". Newsweek. September 13, 2021. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ Choi, Joseph (August 15, 2021). "Blinken on Afghanistan: 'This is not Saigon'". The Hill. Archived from the original on August 18, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ "Top US diplomat decries 'ethnic cleansing' in Ethiopia's Tigray". Al Jazeera. March 10, 2021. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "The World's Deadliest War Isn't in Ukraine, But in Ethiopia". The Washington Post. March 23, 2022. Archived from the original on November 10, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Scoop: Biden won't reverse Trump's Western Sahara move, U.S. tells Morocco". Axios. April 30, 2021. Archived from the original on May 3, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Why Biden's Western Sahara policy remains under review". Al-Jazeera. June 13, 2021. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Blinken praises Ethiopia on Tigray peace, no return to trade programme yet". Reuters. March 15, 2023.

- ^ "Secretary Blinken's Call with Venezuelan Interim President Guaidó". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- ^ Nunley, Christian (March 10, 2021). "Pentagon chief, secretary of State announce first trips abroad as Biden looks to reset global relations". CNBC. Archived from the original on March 15, 2021. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ Pamuk, Humeyra; Takenaka, Kiyoshi; Park, Ju-min (March 17, 2021). "Blinken warns China against 'coercion and aggression' on first Asia trip". Reuters. Archived from the original on April 14, 2023. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ Toosi, Nahal (March 22, 2021). "U.S., allies announce sanctions on China over Uyghur 'genocide'". Politico. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. and allies accuse China of global hacking spree". Reuters. July 19, 2021. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ Cheung, Eric (April 1, 2021). "Hong Kong court convicts media tycoon Jimmy Lai and other activists over peaceful protest". CNN. Archived from the original on April 1, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ "Sentencing of Hong Kong Pro-Democracy Activists for Unlawful Assembly". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ "Blinken warns China threat greater than Russia long term". Deutsche Welle. May 26, 2022. Archived from the original on April 3, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "US's Blinken raises China's 'alignment with Russia' on Ukraine". Al Jazeera. July 9, 2022. Archived from the original on March 20, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Secretary Blinken's Visit to the People's Republic of China (PRC)". June 19, 2023. Retrieved June 19, 2023.

- ^ "Travel to United Kingdom and Ukraine, May 3–6, 2021". United States Department of State. Retrieved April 25, 2021.

- ^ "Travel to Denmark, Iceland, and Greenland, May 16–20, 2021". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on May 17, 2021. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ Hansler, Jennifer (May 6, 2021). "Blinken says US 'actively looking' at boosting security cooperation with Ukraine during trip to Kiev". CNN. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ "The Latest: Netanyahu raps 'anarchy' of Jewish-Arab fighting". Associated Press. May 13, 2021. Archived from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ Tidman, Zoe (May 28, 2021). "US 'warns Israeli leaders evicting Palestinians could spark war'". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on May 30, 2021. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ "Egyptian mediators try to build on Israel-Hamas ceasefire". Reuters. May 22, 2021. Archived from the original on May 22, 2021. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ Graham-Harrison, Emma; Borger, Julian (May 25, 2021). "'US to reopen Palestinian diplomatic mission in Jerusalem". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 26, 2021. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- ^ a b Zengerle, Patricia (June 7, 2021). "Blinken: U.S. able to mitigate Nord Stream 2 pipeline effects". Reuters. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ Price, Ned (June 9, 2021). "Travel to the United Kingdom, Belgium, and Switzerland, June 9–15, 2021". Archived from the original on June 12, 2021. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ a b Clark, Joseph (June 13, 2021). "Blinken says U.S.-Russia relations at a low point going into summit". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on June 15, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- ^ Price, Ned (June 13, 2021). "Secretary Antony J. Blinken with Chris Wallace of Fox News Sunday". Archived from the original on June 15, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- ^ "EU Eyes May In-Person Meeting of U.S. Technology Council". Bloomberg.com. January 27, 2022. Archived from the original on May 18, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ "Blinken Authorizes Baltic Countries to Send US Weapons to Ukraine". VOA. January 22, 2022. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- ^ "US sends first military aid shipment to Ukraine amid Russia standoff". euronews. January 22, 2022. Archived from the original on March 15, 2023. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- ^ "Secretary Antony J. Blinken and Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba at a Joint Press Availability". United States Department of State. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ^ "Blinken says Russia could invade Ukraine during Olympics". ABC News. February 11, 2022. Archived from the original on August 25, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Ukraine tensions: US defends evacuating embassy as Zelensky urges calm". BBC News. February 13, 2022. Archived from the original on February 13, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Blinken, in Kyiv, pledges to support Ukraine 'for as long as it takes'". The Washington Post. September 8, 2022. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Blinken: US has told Russia to 'stop the loose talk' on nuclear weapons". The Hill. September 25, 2022. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Antony Blinken Tried to Convince China to Reject Russia. It Went About as Well as You'd Expect". Mother Jones. July 9, 2022. Archived from the original on March 21, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "U.S., Russian Defense Ministers Discuss Ukraine Invasion In Rare Phone Call". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. October 21, 2022. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. sees no evidence Russia is interested in ending Ukraine aggression - Blinken". Reuters. October 21, 2022. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved October 21, 2022.

- ^ "Putin welcomes China's controversial proposals for peace in Ukraine". The Guardian. March 21, 2023. Archived from the original on April 12, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Blinken says no Ukraine cease-fire without a peace deal that includes Russia's withdrawal". CNBC. June 3, 2023.

- ^ "Ukraine says cluster munitions will be 'game changer' against Russia". Politico. July 11, 2023.

- ^ "Anger as families of US detainees in Middle East left off Blinken call". the Guardian. July 5, 2022. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved July 29, 2022.

- ^ "Blinken says he 'pressed' Lavrov on release of US prisoners". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved July 29, 2022.

- ^ Atwood, Kylie; Hansler, Jennifer (June 23, 2022). "Families of unlawfully detained Americans left with mixed emotions after Blinken tried to reassure them in call | CNN Politics". CNN. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved October 22, 2022.

- ^ Kaplan, Thomas (October 30, 2020). "Who Has Biden's Ear on Policy Issues? A Largely Familiar Inner Circle". The New York Times. p. A23. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ "Biden's Foreign Policy Picks Are from the Hawkish National Security Blob. That is a Bad Sign". November 23, 2020.

- ^ Dershowitz, Toby; Kittrie, Orde (June 21, 2020). "Biden blasts BDS: Why it matters". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ a b Kornbluh, Jacob (October 28, 2020). "Tony Blinken's Biden spiel". Jewish Insider. Archived from the original on November 21, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Lacy, Akela (November 18, 2020). "On Arms Sales to Dictators and the Yemen War, Progressives See a Way In With Biden". The Intercept. Archived from the original on November 22, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Magid, Jacob (October 29, 2020). "Top Biden foreign policy adviser 'concerned' over planned F-35 sale to UAE". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on November 5, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ "Biden's State pick backs two-state solution, says US embassy stays in Jerusalem". The Times of Israel. Agence France-Presse. January 19, 2021. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ^ "Biden to nominate Antony Blinken as US secretary of state". Al Jazeera. November 23, 2020. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Lake, Eli (January 22, 2021). "Biden's First Foreign Policy Blunder Could Be on Iran". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ "Backing 'every' option against Iran, Blinken appears to nod at military action". The Times of Israel. October 14, 2021. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Blinken Declines to Rule Out Military Option Should Iran Nuclear Talks Fail". Haaretz. October 31, 2021. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ Galloway, Anthony (November 23, 2020). "Biden's pick for the next secretary of state is Australia's choice too". Brisbane Times. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Barnes, Julian E.; Jakes, Lara; Steinhauer, Jennifer (January 20, 2021). "In Confirmation Hearings, Biden Aides Indicate Tough Approach on China". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ^ a b Fromer, Jacob (January 20, 2021). "Top US diplomat nominee says Trump's China approach was right, tactics wrong". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. secretary of state nominee Blinken sees strong foundation for bipartisan China policy". Reuters. January 19, 2021. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ a b Shalal, Andrea (September 22, 2020). "Biden adviser says unrealistic to 'fully decouple' from China". Reuters. Archived from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Thomas, Ken (November 23, 2020). "Joe Biden Picks Antony Blinken for Secretary of State". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 2462827440. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ "US-Greece security relationship key to American interests in East Med, says Blinken". Kathimerini. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ @ABlinken (October 27, 2020). "We regret calls by Turkish President Erdogan and Turkish Cypriot leader Tatar for a two-state solution in Cyprus. Joe Biden has long expressed support for a bizonal, bicommunal federation that ensures peace and prosperity for all Cypriots" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "US secretary of state nominee Blinken says Turkey not acting like an ally". Kathimerini. January 20, 2021. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Secretary-designate Blinken Says NATO Door Shall Remain Open to Georgia Archived January 22, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Civil Georgia

- ^ Pifer, Steven (December 1, 2020). "Reviving nuclear arms control under Biden". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- ^ "Incoming US Secretary of State Antony Blinken voices support for Armenia and Republic of Artsakh". Public Radio of Armenia. January 22, 2021. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Borger, Julian (November 23, 2020). "Antony Blinken: Biden's secretary of state nominee is sharp break with Trump era". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- ^ Colson, Thomas (November 3, 2020). "Joe Biden's Secretary of State pick Tony Blinken said Brexit was like a dog being run over by a car and a 'total mess'". Business Insider. Archived from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- ^ Dettmer, Jamie (November 24, 2020). "Egyptian Suspects in Murder of Italian Student Likely to Face In-Absentia Trial". Voice of America. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ "Biden aide Blinken voices concern about rights group in Egypt". Reuters. November 20, 2020. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Iqbal, Anwar (August 16, 2021). "US to recognise Taliban only if they respect basic rights, says Blinken". DAWN.COM. Archived from the original on August 16, 2021. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ Hansler, Jennifer (October 12, 2023). "Blinken pledges US will never falter from supporting Israel as he likens Hamas' crimes to ISIS". CNN. Archived from the original on November 13, 2023.

- ^ Harb, Ali (November 4, 2023). "What's behind Antony Blinken's call for 'humanitarian pauses' in Gaza?". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on December 16, 2023.

- ^ Sennett, Ellie; Issawy, Ahmed (February 12, 2024). "'Kibbutz Blinken': Meet the pro-Palestine protesters occupying Secretary of State's street". The National. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ Kaplan, Allison (November 22, 2020). "Long-time Biden aide Blinken most likely choice for secretary of state". Haaretz. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- ^ Herszenhorn, David (November 23, 2020). "Nine things to know about Antony Blinken". Politico. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- ^ Sevastopulo, Demetri (November 23, 2020). "Biden's 'alter ego' Antony Blinken tipped for top foreign policy job". Financial Times. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Shaffer, Claire (November 23, 2020). "Yes, Biden's Secretary of State Hopeful Antony Blinken Has a Band". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Thompson, Stephen; Martin, Michel (November 28, 2020). "Music Review: Secretary of State Pick Antony Blinken". NPR. All Things Considered. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ "US Secretary of State Antony Blinken sings the blues". BBC News. September 28, 2023.

- ^ Crowley, Michael (October 2, 2023). "When Mr. Secretary Loves to Rock". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 2, 2023. Retrieved December 5, 2023.

- ^ "Blinken sings for musical diplomacy". www.washingtonpost.com. Retrieved December 5, 2023.

- ^ Kurtz, Judy (September 28, 2023). "Blinken kicks off State Deparment music diplomacy initiative with his own performance". The Hill. Retrieved December 5, 2023.

- ^ "Michèle Flournoy". WestExec Advisors. October 19, 2017. Archived from the original on November 15, 2020. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- ^ "Our Team". WestExec Advisors. January 11, 2016. Archived from the original on May 10, 2020. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- ^ a b c Lipton, Eric; Vogel, Kenneth P. (November 28, 2020). "Biden Aides' Ties to Consulting and Investment Firms Pose Ethics Test". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- ^ Guyer, Jonathan (July 6, 2020). "How Biden's Foreign-Policy Team Got Rich". The American Prospect. Archived from the original on July 18, 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ Detsch, Jack; Gramer, Robbie (November 23, 2020). "Biden's Likely Defense Secretary Pick Flournoy Faces Progressive Pushback". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Vogel, Kenneth P.; Lipton, Eric (January 2, 2021). "Washington Has Been Lucrative for Some on Biden's Team". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ a b Fang, Lee (July 22, 2018). "Former Obama Officials Help Silicon Valley Pitch the Pentagon for Lucrative Defense Contracts". The Intercept. Archived from the original on May 15, 2020. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- ^ Shorrock, Tim (September 21, 2020). "Progressives Slam Biden's Foreign Policy Team". The Nation. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ "Antony Blinken". Pine Island Capital Partners. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- ^ a b c Ackerman, Spencer; Markay, Lachlan; Schactman, Noah (December 8, 2020). "Firm Tied to Team Biden Looks to Cash In On COVID Response". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on December 12, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- ^ a b "The Revolving Door: Biden's National Security Nominees Cashed In on Government Service – and Now They're Back". Common Dreams. November 28, 2020. Archived from the original on November 29, 2020. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- ^ "Team". Pine Island Capital Partners. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- ^ "Membership Roster". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on February 8, 2019. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ "Antony J. Blinken". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ "Tony Blinken – Spring 2017 Resident Fellow". University of Chicago Institute of Politics. 2017. Archived from the original on April 8, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

External links

- Biography at the United States Department of State

- Biography at the United States Department of State (2009–2017, archived)

- Confirmation hearing for U.S. Secretary of State from the Senate Foreign Relations Committee (January 19, 2021)

- Profile at the Wayback Machine (archived January 20, 2021) from WestExec Advisors

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Antony Blinken on Twitter

- 1962 births

- Living people

- People from Yonkers, New York

- Blinken family

- United States Deputy National Security Advisors

- United States Deputy Secretaries of State

- United States Secretaries of State

- Obama administration personnel

- Biden administration cabinet members

- American people of Hungarian-Jewish descent

- American people of Ukrainian-Jewish descent

- Columbia Law School alumni

- Dalton School alumni

- Harvard College alumni

- The Harvard Crimson people

- Jewish American members of the Cabinet of the United States

- New York (state) Democrats

- 20th-century American diplomats

- 21st-century American diplomats

- 21st-century American politicians

- Biden administration personnel

.jpg/100px-Joe_Biden_presidential_portrait_(cropped).jpg)