Palestinian National Authority

Palestinian National Authority السلطة الوطنية الفلسطينية as-Sulṭa al-Waṭanīya al-Filasṭīnīya | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: "فدائي" "Fida'i"[1] "Fedayeen Warrior" | |

![The Palestinian Authority exerts partial civil control in 167 islands in the West Bank and in the Gaza Strip[2]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/de/Zones_A_and_B_in_the_occupied_palestinian_territories.svg/250px-Zones_A_and_B_in_the_occupied_palestinian_territories.svg.png) The Palestinian Authority exerts partial civil control in 167 islands in the West Bank and in the Gaza Strip[2] | |

| Administrative center | Ramallah 31°54′N 35°12′E / 31.900°N 35.200°E |

| Largest city | Gaza 31°31′N 34°27′E / 31.517°N 34.450°E |

| Official languages | Arabic |

| Type | Provisional self-government body |

| Government | Semi‑presidential[3] |

| Mahmoud Abbas | |

| Vacant | |

| Legislature | Legislative Council |

| Partial delegation of civil powers from Israeli administration | |

| 13 September 1993 | |

| 1994 | |

| 1995 | |

| 2007 | |

| 29 November 2012 | |

| Currency |

|

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Calling code | +970 |

| ISO 3166 code | PS |

| Internet TLD | .ps |

The Palestinian National Authority (PA or PNA; Arabic: السلطة الوطنية الفلسطينية as-Sulṭa al-Waṭanīya al-Filasṭīnīya), commonly known as the Palestinian Authority and officially the State of Palestine,[6] is the Fatah-controlled government body that exercises partial civil control over West Bank areas "A" and "B" as a consequence of the 1993–1995 Oslo Accords.[2][7][8] The Palestinian Authority controlled the Gaza Strip prior to the Palestinian elections of 2006 and the subsequent Gaza conflict between the Fatah and Hamas parties, when it lost control to Hamas; the PA continues to claim the Gaza Strip, although Hamas exercises de facto control. Since January 2013, the Palestinian Authority has used the name "State of Palestine" on official documents, although the United Nations continues to recognize the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) as the "representative of the Palestinian people".[9]

The Palestinian Authority was formed in 1994, pursuant to the Gaza–Jericho Agreement between the PLO and the government of Israel, and was intended to be a five-year interim body. Further negotiations were then meant to take place between the two parties regarding its final status. According to the Oslo Accords, the Palestinian Authority was designated to have exclusive control over both security-related and civilian issues in Palestinian urban areas (referred to as "Area A") and only civilian control over Palestinian rural areas ("Area B"). The remainder of the territories, including Israeli settlements, the Jordan Valley region and bypass roads between Palestinian communities, were to remain under Israeli control ("Area C"). East Jerusalem was excluded from the Accords. Negotiations with several Israeli governments had resulted in the Authority gaining further control of some areas, but control was then lost in some areas when the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) retook several strategic positions during the Second ("Al-Aqsa") Intifada. In 2005, after the Second Intifada, Israel withdrew unilaterally from its settlements in the Gaza Strip, thereby expanding Palestinian Authority control to the entire strip[10] while Israel continued to control the crossing points, airspace, and the waters of the Gaza Strip's coast.[11]

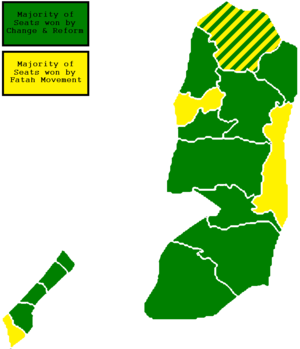

In the Palestinian legislative elections on 25 January 2006, Hamas emerged victorious and nominated Ismail Haniyeh as the Authority's Prime Minister. However, the national unity Palestinian government effectively collapsed, when a violent conflict between Hamas and Fatah erupted, mainly in the Gaza Strip. After the Gaza Strip was taken over by Hamas on 14 June 2007, the Authority's Chairman Mahmoud Abbas dismissed the Hamas-led unity government and appointed Salam Fayyad as Prime Minister, dismissing Haniyeh. The move wasn't recognized by Hamas, thus resulting in two separate administrations – the Fatah-led Palestinian Authority in the West Bank and a rival Hamas government in the Gaza Strip. The reconciliation process to unite the Palestinian governments achieved some progress over the years, but had failed to produce a re-unification.

The Palestinian Authority received financial assistance from the European Union and the United States (approximately US$1 billion combined in 2005). All direct aid was suspended on 7 April 2006, as a result of the Hamas victory in parliamentary elections.[12][13] Shortly thereafter, aid payments resumed, but were channeled directly to the offices of Mahmoud Abbas in the West Bank.[14] Since 9 January 2009, when Mahmoud Abbas' term as president was supposed to have ended and elections were to have been called, Hamas supporters and many in the Gaza Strip have withdrawn recognition for his presidency and instead consider Aziz Dweik, the speaker of the Palestinian Legislative Council, to be the acting president until new elections can be held.[15][16]

The State of Palestine has become recognized by 138 nations and since November 2012, the United Nations voted to recognize the State of Palestine as a non-member UN observer state.[17][18][19] The Palestinian Authority is an authoritarian regime that has not held elections in over 15 years; it has been criticized for human rights abuses, including cracking down on journalists, human rights activists, and dissent against its rule.[20]

History

Establishment

The Palestinian Authority was created by the Gaza–Jericho Agreement, pursuant to the 1993 Oslo Accords. The Gaza–Jericho Agreement was signed on 4 May 1994 and included Israeli withdrawal from the Jericho area and partially from the Gaza Strip, and detailed the creation of the Palestinian Authority and the Palestinian Civil Police Force.[7][8]

The PA was envisioned as an interim organization to administer a limited form of Palestinian self-governance in the Palestinian enclaves in the West Bank and Gaza Strip for a period of five years, during which final-status negotiations would take place.[21][22][23] The Palestinian Central Council, itself acting on behalf of the Palestine National Council of the PLO, implemented this agreement in a meeting convened in Tunis from 10 to 11 October 1993, making the Palestinian Authority accountable to the PLO Executive Committee.[24]

The administrative responsibilities accorded to the PA were limited to civil matters and internal security and did not include external security or foreign affairs.[25] Palestinians in the diaspora and inside Israel were not eligible to vote in elections for the offices of the Palestinian Authority.[26] The PA was legally separate from the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), which continues to enjoy international recognition as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people, representing them at the United Nations under the name "Palestine".[27][28]

General elections were held for its first legislative body, the Palestinian Legislative Council, on 20 January 1996.[24] The expiration of the body's term was 4 May 1999, but elections were not held because of the "prevailing coercive situation".[24]

Second Intifada

On 7 July 2004, the Quartet of Middle East mediators informed Ahmed Qurei, Prime Minister of the PA from 2003 to 2006, that they were "sick and tired" of the Palestinians failure to carry out promised reforms: "If security reforms are not done, there will be no (more) international support and no funding from the international community"[29]

On 18 July 2004, United States President George W. Bush stated that the establishment of a Palestinian state by the end of 2005 was unlikely due to instability and violence in the Palestinian Authority.[30]

Following Arafat's death on 11 November 2004, Rawhi Fattouh, leader of the Palestinian Legislative Council became Acting President of the Palestinian Authority as provided for in Article 54(2) of the Authority's Basic Law and Palestinian Elections Law.[31]

On 19 April 2005, Vladimir Putin the president of Russia agreed to aid the Palestinian Authority stating, "We support the efforts of President Abbas to reform the security services and fight against terrorism [...] If we are waiting for President Abbas to fight terrorism, he cannot do it with the resources he has now. [...] We will give the Palestinian Authority technical help by sending equipment, training people. We will give the Palestinian Authority helicopters and also communication equipment."[32]

The Palestinian Authority became responsible for civil administration in some rural areas, as well as security in the major cities of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Although the five-year interim period expired in 1999, the final status agreement has yet to be concluded despite attempts such as the 2000 Camp David Summit, the Taba Summit, and the unofficial Geneva Accords.

In August 2005, Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon began his disengagement from the Gaza Strip, ceding full effective internal control of the Strip to the Palestinian Authority but retained control of its borders including air and sea (except for the Egyptian border). This increased the percentage of land in the Gaza Strip nominally governed by the PA from 60 percent to 100 percent.

Hamas–Fatah conflict

Palestinian legislative elections took place on 25 January 2006. Hamas was victorious and Ismail Haniyeh was nominated as Prime Minister on 16 February 2006 and sworn in on 29 March 2006. However, when a Hamas-led Palestinian government was formed, the Quartet (United States, Russia, United Nations, and European Union) conditioned future foreign assistance to the Palestinian Authority (PA) on the future government's commitment to non-violence, recognition of the State of Israel, and acceptance of previous agreements. Hamas rejected these demands,[33] which resulted in the Quartet suspension of its foreign assistance program and Israel imposed economic sanctions.

In December 2006, Ismail Haniyeh, Prime Minister of the PA, declared that the PA will never recognize Israel: "We will never recognize the usurper Zionist government and will continue our jihad-like movement until the liberation of Jerusalem."[34]

In an attempt to resolve the financial and diplomatic impasse, the Hamas-led government together with Fatah Chairman Mahmoud Abbas agreed to form a unity government. As a result, Haniyeh resigned on 15 February 2007 as part of the agreement. The unity government was finally formed on 18 March 2007 under Prime Minister Ismail Haniyeh and consisted of members from Hamas, Fatah and other parties and independents. The situation in the Gaza strip however quickly deteriorated into an open feud between the Hamas and Fatah, which eventually resulted in the Brothers' War.

After the takeover in Gaza by Hamas on 14 June 2007, Palestinian Authority Chairman Abbas dismissed the government and on 15 June 2007 appointed Salam Fayyad Prime Minister to form a new government. Though the new government's authority is claimed to extend to all Palestinian territories, in effect it became limited to the Palestinian Authority-controlled areas of the West Bank, as Hamas hasn't recognized the move. The Fayyad government has won widespread international support. Egypt, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia said in late June 2007 that the West Bank-based Cabinet formed by Fayyad was the sole legitimate Palestinian government, and Egypt moved its embassy from Gaza to the West Bank.[35] Hamas, which government has an effective control of the Gaza Strip since 2007, faces international diplomatic and economic isolation.

In 2013, political analyst Hillel Frisch from Bar-Ilan University's BESA Center, noted that "The PA is playing a double game...with regards to battling Hamas, there's coordination if not cooperation with Israel. But on the political front, the PA is trying to generate a popular intifada."[36]

Two PNA administrations

Since the Hamas-Fatah split in 2007, the Fatah-dominated Palestinian Authority based in areas of the West Bank had stabilized, though no significant economic growth had been achieved. Until 2012, there had also been no progress in promotion of PNA status in the UN, as well in negotiations with Israel. Ramallah-based Palestinian Authority stayed out of the Gaza War in 2008–2009, which followed the six-month truce, between Hamas and Israel which ended on 19 December 2008.[37][38][39] Hamas claimed that Israel broke the truce on 4 November 2008,[40][41] though Israel blamed Hamas for an increasing rocket fire directed at southern Israeli towns and cities.[42] The 2008–2009 Israel–Gaza conflict began on 27 December 2008 (11:30 a.m. local time; 09:30 UTC).[43] Though condemning Israel over attacks on Gaza, the Palestinian Authority erected no actions during the conflict of Israel with Hamas.

The reconciliation process between Fatah and Hamas reached intermediate results by the two governments, most notably the agreement in Cairo on 27 April 2011, but with no final solution. Though the two agreed to form a unity government,[44] and to hold elections in both territories within 12 months of the establishment of such a government,[45][46] it had not been implemented. The 2011 deal also promised the entry of Hamas into the Palestine Liberation Organization and holding of elections to its Palestine National Council decision-making body, which was not implemented as well. The deal was further ratified in the 2012 Hamas–Fatah Doha agreement, which was made with the background of Hamas relocation from Damascus, due to the simmering Syrian civil war.

Since late August 2012, Palestinian National Authority has been swept with social protests aiming against the cost of living. The protesters targeted the Palestinian Prime Minister Salam Fayyad, calling for his resignation. Some anti-government protests turned violent.[47] On 11 September, Palestinian Prime Minister issued a decree on lowering the fuel prices and cutting salaries of top officials.[47]

In July 2012, it was reported that Hamas Government in Gaza was considering to declare the independence of the Gaza Strip with the help of Egypt.[48]

On 23 April 2014 Ismail Haniyeh, the prime minister of Hamas, and a senior Palestine Liberation Organisation delegation dispatched by Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas signed the Fatah–Hamas Gaza Agreement at Gaza City in an attempt to create reconciliation in the Fatah–Hamas conflict.[49] It stated that a unity government should be formed within five weeks, ahead of a presidential and parliamentary election within six months.[50] The Palestinian unity government of 2014 formed on 2 June 2014 as a national and political union under Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas. The European Union, the United Nations, the United States, China, India, Russia and Turkey all agreed to work with it.[51][52][53][54] The Israeli government condemned the unity government because it views Hamas as a terrorist organization.[55][56] The Palestinian unity government first convened in Gaza on 9 October 2014 to discuss the reconstruction of the Gaza Strip following the 2014 Israel–Gaza conflict. On 30 November 2014, Hamas declared that the unity government had ended with the expiration of the six-month term.[57][58] But Fatah subsequently denied the claim, and said that the government is still in force.[59]

On 7–8 February 2016, Fatah and Hamas held talks in Doha, Qatar in an attempt to implement the 2014 agreements. Hamas official told Al-Monitor on 8 March, that the talks did not succeed and that discussions continued between the two movements. He also said that the foreign pressures on the Palestinian Authority to not implement the reconciliation terms is the main obstacle in the talks. In a 25 Feb statement to local newspaper Felesteen, Hamas foreign relations chief Osama Hamdan accused the United States and Israel of blocking Palestinian reconciliation. The United States is putting pressure on the PA to not reconcile with Hamas until the latter recognizes the Quartet on the Middle East's conditions, including the recognition of Israel, which Hamas rejects. After the 2014 agreement, US President Barack Obama said in April 2014 that President Mahmoud Abbas' decision to form a national unity government with Hamas was "unhelpful" and undermined the negotiations with Israel. Amin Maqboul, secretary-general of Fatah's Revolutionary Council, told Al-Monitor, "Hamas did not stick to the 2014 agreement, as it has yet to hand over the reins of power over Gaza to the national consensus government and continues to control the crossings. Should Hamas continue down this path, we have to go to the polls immediately and let the people choose who they want to rule".[60]

2013 name change

The UN has permitted the PLO to title its representative office to the UN as "The Permanent Observer Mission of the State of Palestine to the United Nations",[18] and Palestine has started to re-title its name accordingly on postal stamps, official documents and passports,[6][61] whilst it has instructed its diplomats to officially represent 'The State of Palestine', as opposed to the 'Palestine National Authority'.[6] Additionally, on 17 December 2012, UN Chief of Protocol Yeocheol Yoon decided that "the designation of 'State of Palestine' shall be used by the Secretariat in all official United Nations documents".[17] However, in a speech in 2016 president Abbas said that "The Palestinian Authority exists and it is here," and "The Palestinian Authority is one of our achievements and we won't give it up."[62]

2024 mass resignation

On the morning of 26 February 2024, the entire Palestinian government, including Prime Minister Mohammad Shtayyeh, resigned from office, amid popular opposition to the Palestinian Authority and pressure from the United States during the Israel–Hamas war.[63][64][65][66]

Geography

The Palestinian Territories refers to the Gaza Strip and the West Bank (including East Jerusalem). The Palestinian Authority currently administers some 39% of the West Bank. 61% of the West Bank remains under direct Israeli military and civilian control. East Jerusalem was unilaterally annexed by Israel in 1980, prior to the formation of the PA. Since 2007 Gaza has been governed by the Hamas Government in Gaza.

Politics and internal structure

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2016) |

The politics of the Palestinian Authority take place within the framework of a semi-presidential multi-party republic, with the Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC), an executive President, and a Prime Minister leading a Cabinet. According to the Palestinian Basic Law which was signed by Arafat in 2002 after a long delay, the current structure of the PA is based on three separate branches of power: executive, legislative, and judiciary.[67] The PA was created by, is ultimately accountable to, and has historically been associated with, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), with whom Israel negotiated the Oslo Accords.[24]

The PLC is an elected body of 132 representatives, which must confirm the Prime Minister upon nomination by the President, and which must approve all government cabinet positions proposed by the Prime Minister. The Judicial Branch has yet to be formalized. The President of the PA is directly elected by the people, and the holder of this position is also considered to be the commander-in-chief of the armed forces. In an amendment to the Basic Law approved in 2003, the president appoints the Prime Minister who is also chief of the security services in the Palestinian territories. The Prime Minister chooses a cabinet of ministers and runs the government, reporting directly to the President.[citation needed]

Parliamentary elections were conducted in January 2006 after the passage of an overhauled election law that increased the number of seats from 88 to 132.[68] The Chairman of the PLO, Yasser Arafat, was elected as President of PA in a landslide victory at the general election in 1996.

Arafat's administration was criticized for its lack of democracy, widespread corruption among officials, and the division of power among families and numerous governmental agencies with overlapping functions.[69] Both Israel and the US declared they lost trust in Arafat as a partner and refused to negotiate with him, regarding him as linked to terrorism.[70] Arafat denied this, and was visited by other leaders around the world up until his death. However, this began a push for change in the Palestinian leadership. In 2003, Mahmoud Abbas resigned because of lack of support from Israel, the US, and Arafat himself.[71] He won the presidency on 9 January 2005 with 62% of the vote. Former prime minister Ahmed Qureia formed his government on 24 February 2005 to wide international praise because, for the first time, most ministries were headed by experts in their field as opposed to political appointees.[72]

The presidential mandate of Mahmoud Abbas expired in 2009 and he is no longer recognised by Hamas, among others, as the legitimate Palestinian leader. According to Palestinian documents leaked to the Al Jazeera news organization, the United States has threatened to cut off funding to the Palestinian Authority should there be a change in the Palestinian leadership in the West Bank.[73] In February 2011, the Palestinian Authority announced that parliamentary and presidential elections would be held by September 2011.[74]

On 27 April 2011, Fatah's Azzam al-Ahmad announced the party's signing of a memorandum of understanding with Hamas' leadership, a major step towards reconciliation effectively paving the way for a unity government.[44] The deal was formally announced in Cairo, and was co-ordinated under the mediation of Egypt's new intelligence director Murad Muwafi.[75] The deal came amidst an international campaign for statehood advanced by the Abbas administration, which is expected to culminate in a request for admission into the General Assembly as a member state in September.[76] As part of the deal, the two factions agreed to hold elections in both territories within twelve months of the creation of a transitional government.[45] In response to the announcement, Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu warned that the Authority must choose whether it wants "peace with Israel or peace with Hamas".[44][75]

Officials

| Office | Name | Party | Since |

|---|---|---|---|

| President | Mahmoud Abbas | Fatah | 26 January 2005 – incumbent |

| Yasser Arafat | Fatah | 5 July 1994 – 11 November 2004 | |

| Prime Minister | Mohammad Shtayyeh | Fatah | 14 April 2019 – incumbent[77] |

| Rami Hamdallah | Fatah | 2 June 2014 – 14 April 2019 | |

| Rami Hamdallah | Fatah | 6 June 2013 – 2 June 2014 (disputed) | |

| Salam Fayyad | Independent | 14 June 2007 – 6 June 2013 | |

| Ismaïl Haniyeh | Hamas | 19 February 2006 – 14 June 2007 | |

| Ahmad Qurei | Fatah | 24 December 2005 – 19 February 2006 | |

| Nabil Shaath | Fatah | 15 December 2005 – 24 December 2005 | |

| Ahmad Qurei | Fatah | 7 October 2003 – 15 December 2005 | |

| Mahmoud Abbas | Fatah | 19 March 2003 – 7 October 2003 |

Political parties and elections

From the establishment of the Palestinian Authority in 1993 until the death of Yasser Arafat in late 2004, only one election had taken place. All other elections were deferred for various reasons.

A single election for president and the legislature took place in 1996. The next presidential and legislative elections were scheduled for 2001 but were delayed following the outbreak of the Al-Aqsa Intifada. Following Arafat's death, elections for the President of the Authority were announced for 9 January 2005. The PLO leader Mahmoud Abbas won 62.3% of the vote, while Dr. Mustafa Barghouti, a physician and independent candidate, won 19.8%.[78]

| Candidate | Party | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mahmoud Abbas | Fatah | 501,448 | 67.38 | |

| Mustafa Barghouti | Independent | 156,227 | 20.99 | |

| Taysir Khalid | Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine | 26,848 | 3.61 | |

| Abelhaleem Hasan Abdelraziq Ashqar | Independent | 22,171 | 2.98 | |

| Bassam as-Salhi | Palestinian People's Party | 21,429 | 2.88 | |

| Sayyid Barakah | Independent | 10,406 | 1.40 | |

| Abdel Karim Shubeir | Independent | 5,717 | 0.77 | |

| Total | 744,246 | 100.00 | ||

| Valid votes | 744,246 | 92.79 | ||

| Invalid/blank votes | 57,831 | 7.21 | ||

| Total votes | 802,077 | 100.00 | ||

| Registered voters/turnout | 1,092,407 | 73.42 | ||

| Source: IFES | ||||

On 10 May 2004, the Palestinian Cabinet announced that municipal elections would take place for the first time. Elections were announced for August 2004 in Jericho, followed by certain municipalities in the Gaza Strip. In July 2004 these elections were postponed. Issues with voter registration are said to have contributed to the delay. Municipal elections finally took place for council officials in Jericho and 25 other towns and villages in the West Bank on 23 December 2004. On 27 January 2005, the first round of the municipal elections took place in the Gaza Strip for officials in 10 local councils. Further rounds in the West Bank took place in May 2005.

Elections for a new Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC) were scheduled for July 2005 by Acting Palestinian Authority President Rawhi Fattuh in January 2005. These elections were postponed by Mahmoud Abbas after major changes to the Election Law were enacted by the PLC which required more time for the Palestinian Central Elections Committee to process and prepare. Among these changes were the expansion of the number of parliament seats from 88 to 132, with half of the seats to be competed for in 16 localities, and the other half to be elected in proportion to party votes from a nationwide pool of candidates.

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Proportional | District | Total seats | |||||

| Votes | % | Seats | Votes | % | Seats | |||

| Change and Reform (Hamas) | 440,409 | 44.45 | 29 | 1,932,168 | 40.82 | 45 | 74 | |

| Fatah | 410,554 | 41.43 | 28 | 1,684,441 | 35.58 | 17 | 45 | |

| Martyr Abu Ali Mustafa | 42,101 | 4.25 | 3 | 140,074 | 2.96 | 0 | 3 | |

| The Alternative | 28,973 | 2.92 | 2 | 8,216 | 0.17 | 0 | 2 | |

| Independent Palestine | 26,909 | 2.72 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Third Way | 23,862 | 2.41 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Palestinian Popular Struggle Front | 7,127 | 0.72 | 0 | 8,821 | 0.19 | 0 | 0 | |

| Palestinian Arab Front | 4,398 | 0.44 | 0 | 3,446 | 0.07 | 0 | 0 | |

| Martyr Abu al-Abbas | 3,011 | 0.30 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| National Coalition for Justice and Democracy | 1,806 | 0.18 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Palestinian Justice | 1,723 | 0.17 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Palestinian Democratic Union | 3,257 | 0.07 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Independents | 953,465 | 20.14 | 4 | 4 | ||||

| Total | 990,873 | 100.00 | 66 | 4,733,888 | 100.00 | 66 | 132 | |

| Valid votes | 990,873 | 95.05 | 1,000,246 | 95.95 | ||||

| Invalid votes | 29,864 | 2.86 | 31,285 | 3.00 | ||||

| Blank votes | 21,687 | 2.08 | 10,893 | 1.04 | ||||

| Total votes | 1,042,424 | 100.00 | 1,042,424 | 100.00 | ||||

| Registered voters/turnout | 1,350,655 | 77.18 | 1,350,655 | 77.18 | ||||

| Source: CEC | ||||||||

The following organizations, listed in alphabetic order, have taken part in recent popular elections inside the Palestinian Authority:

- Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (Al-Jabhah al-Dimuqratiyah Li-Tahrir Filastin)

- Fatah or Liberation Movement of Palestine (Harakat al-Tahrâr al-Filistini)

- Hamas or Islamic Resistance Movement (Harakat al-Muqawamah al-Islamiyah)

- Palestine Democratic Union (al-Ittihad al-Dimuqrati al-Filastini, FiDA)

- Palestinian National Initiative (al-Mubadara al-Wataniya al-Filistiniyya)

- Palestinian People's Party (Hizb al-Sha'b al-Filastini)

- Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (Al-Jabhah al-sha'abiyah Li-Tahrir Filastin)

October 2006 polls showed that Fatah and Hamas had equal strength.[79]

On 14 June 2007, after the Battle of Gaza (2007), Palestine president Mahmoud Abbas dismissed the Hamas-led government, leaving the government under his control for 30 days, after which the temporary government had to be approved by the Palestinian Legislative Council.[80]

Law

Human rights

In theory the Palestinian Authority has guaranteed freedom of assembly to the Palestinian citizens residing in its territory. Nevertheless, the right to demonstrate for opponents of the PA regime or of PA policy has become increasingly subject to police control and restriction and is a source of concern for human rights groups.[81] In August 2019, the Palestinian Authority banned LGBTQ organizations from operating in the West Bank, targeting the group Al Qaws.[82]

The Fatah–Hamas conflict has further limited the freedom of the press in the PA territories and the distribution of opposing voices in Hamas-controlled Gaza and the West Bank where Fatah still has more influence. According to the Ramallah-based Palestinian Center for Development and Media Freedoms, in 2011, there were more assaults on Palestinian press freedom from the PA than from Israel.[83] In July 2010, with the easing of the blockade of the Gaza Strip, Israel allowed the distribution of the pro-Fatah newspapers al-Quds, al-Ayyam and al-Hayat al-Jadida to Gaza, but Hamas prevented Gazan distributors from retrieving the shipment. The Palestinian Centre for Human Rights (PCHR) condemned the Hamas restrictions of distribution of the West Bank newspapers in Gaza, and also condemned the Fatah-led government in the West Bank for restricting publication and distribution of the Gazan newspapers al-Resala and Falastin.[84]

Women have full suffrage in the PA. In the 2006 elections, women made up 47 percent of registered voters. Prior to the elections, the election law was amended to introduce a quota for women on the national party lists, resulting in 22 percent of candidates on the national lists being women. The quota's effectiveness was illustrated in comparison with the district elections, where there was no quota, and only 15 of the 414 candidates were women.[85]

Selling land or housing to Israeli Jews is punishable by death, and some high-profile cases have received high media coverage.[86][87] Although president Mahmoud Abbas has never ratified a death sentence in such cases, as late as December 2018 a Ramallah court sentenced the Palestinian-American Isaam Akel, a resident of East Jerusalem, to life in prison with hard labor for having sold land in the Old City of Jerusalem to Israeli Jews. His family maintained his innocence.[88] The Palestinian governor of East Jerusalem, Adnan Gheith, was arrested twice by Israeli authorities in connection with the case.[89]

Hamas has begun enforcing some Islamic standards of dress for women in the PA; women must don headscarves in order to enter government ministry buildings.[90] In July 2010, Hamas banned the smoking of hookah by women in public. They claimed that it was to reduce the increasing number of divorces.[91]

In June 2011, the Independent Commission for Human Rights published a report whose findings included that the Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip were subjected in 2010 to an "almost systematic campaign" of human rights abuses by the Palestinian Authority and Hamas, as well as by Israeli authorities, with the security forces belonging to the PA and Hamas being responsible for torture, arrests and arbitrary detentions.[92]

Crime and law enforcement

Violence against civilians

The Palestinian Human Rights Monitoring Group reports that through "everyday disagreements and clashes between the various political factions, families and cities that a complete picture of Palestinian society is painted. These divisions have during the course of the al Aqsa Intifada also led to an increasingly violent 'Intrafada'. In the 10-year period from 1993 to 2003, 16% of Palestinian civilian deaths were caused by Palestinian groups or individuals."[93]

Erika Waak reports in The Humanist "Of the total number of Palestinian civilians killed during this period by both Israeli and Palestinian security forces, 16 percent were the victims of Palestinian security forces." Accusations of collaboration with Israel are used to target and kill individual Palestinians: "Those who are convicted have either been caught helping Israelis, spoken out against Arafat, or are involved in rival criminal gangs, and these individuals are hanged after summary trials. Arafat creates an environment where the violence continues while silencing would-be critics, and although he could make the violence impossible, he doesn't stop it."

Freedom House's annual survey of political rights and civil liberties, Freedom in the World 2001–2002, reports "Civil liberties declined due to: shooting deaths of Palestinian civilians by Palestinian security personnel; the summary trial and executions of alleged collaborators by the Palestinian Authority (PA); extrajudicial killings of suspected collaborators by militias; and the apparent official encouragement of Palestinian youth to confront Israeli soldiers, thus placing them directly in harm's way."[94]

Palestinian security forces have, as of March 2005, not made any arrests for the October 2003 killing of three American members of a diplomatic convoy in the Gaza Strip. Moussa Arafat, head of the Palestinian Military Intelligence and a cousin of the former Palestinian Authority Chairman Yasser Arafat has stated that, regarding the United States pressure to arrest the killers; "They know that we are in a very critical position and that clashing with any Palestinian party under the presence of the occupation is an issue that will present many problems for us". Since the October 2003 attack, United States diplomats have been banned from entering the Gaza Strip.[95]

Violence against officials (2001–2004)

On 22 April 2001, Jaweed al-Ghussein, former Chairman of the Palestine National Fund, was abducted from Abu Dhabi, UAE, flown to Arish, Egypt, and driven across the border to Gaza, where he was held hostage by the Palestinian Authority. The Minister of Justice, Freh Abu Mediane, protested and resigned over the illegality. Haider Abdel Shafi, Chief Delegate in the Madrid Peace Process and leading Palestinian, protested at his incarceration and demanded his immediate release. The PCCR (Palestinian Commission on Citizens Rights) took the case up. The Attorney General Sorani declared there was no legality. The Red Cross was denied access to him. Amnesty International asked for his release. The United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention determined he was being held 'manifestly with no legal justification' and appointed a Special Rapporteur on torture.[96][97][98]

On 15 October 2003, three members of a United States diplomatic convoy were killed and additional members of the convoy wounded three kilometers south of the Erez Crossing into the Gaza Strip by a terrorist bomb. The perpetrators remain at large.

In February 2004, Ghassan Shaqawa, the mayor of Nablus, filed his resignation from office in protest of the Palestinian Authority's lack of action against the armed militias rampaging the city and the multiple attempts by some Palestinians to assassinate him. Gaza's police Chief, General Saib al-Ajez would later say: 'This internal conflict between police and militants cannot happen. It is forbidden. We are a single nation and many people know each other and it is not easy to kill someone who is bearing a weapon to defend his nation."[99]

Karen Abu Zayd, deputy commissioner-general for the UN Relief and Works Agency in the Gaza Strip stated on 29 February 2004: "What has begun to be more visible is the beginning of the breakdown of law and order, all the groups have their own militias, and they are very organized. It's factions trying to exercise their powers."[100]

Ghazi al-Jabali, the Gaza Strip Chief of Police, since 1994 has been the target of repeated attacks by Palestinians. In March 2004, his offices were targeted by gunfire. In April 2004, a bomb was detonated destroying the front of his house. On 17 July 2004, he was kidnapped at gunpoint following an ambush of his convoy and wounding of two bodyguards. He was released several hours later.[101] Less than six hours later, Colonel Khaled Abu Aloula, director of military coordination in the southern part of Gaza was abducted.

On the eve of 17 July, Fatah movement members kidnapped 5 French citizens (3 men and 2 women) and held them hostage in Red Crescent Society building in Khan Yunis:

- Palestinian security officials said that the kidnapping was carried out by the Abu al-Rish Brigades, accused of being linked to Palestinian Authority Chairman Yasser Arafat's Fatah faction.[102]

On 18 July, Arafat replaced Ghazi al-Jabali, with his nephew Moussa Arafat, sparking violent riots in Rafah and Khan Yunis in which members of the al-Aqsa Martyrs' Brigades burned PA offices and opened fire on Palestinian policemen. During the riots, at least one Palestinian was killed and a dozen more seriously wounded.

On 20 July 2004 David Satterfield, the second-in-charge at the United States Department of State Near East desk stated in a hearing before the Senate that the Palestinian Authority had failed to arrest the Palestinian terrorists who had murdered three members of an American diplomatic convoy travelling in the Gaza Strip on 15 October 2003. Satterfield stated:

- "There has been no satisfactory resolution of this case. We can only conclude that there has been a political decision taken by the chairman (Yasser Arafat) to block further progress in this investigation."

On 21 July, Nabil Amar, former Minister of Information and a cabinet member and a member of the Palestinian Legislative Council, was shot by masked gunmen, after an interview with a television channel in which he criticized Yasser Arafat and called for reforms in the PA.[103]

Regarding the descent into chaos Cabinet minister Qadura Fares stated on 21 July 2004:

- "Every one of us is responsible. Arafat is the most responsible for the failure. President Arafat failed and the Palestinian government failed, the Palestinian political factions failed."[104]

On 22 July 2004, The United Nations elevated its threat warning level for the Gaza Strip to "Phase Four" (one less than the maximum "Phase Five") and planned to evacuate non-essential foreign staff from the Gaza Strip.[105]

On 23 July 2004, an Arab boy was shot and killed by Palestinian terrorists of the Al-Aqsa Martyrs' Brigades after he and his family physically opposed their attempt to set up a Qassam rocket launcher outside the family's house. Five other individuals were wounded in the incident.[106][107][108][109]

On 31 July, Palestinian kidnappers in Nablus seized 3 foreign nationals, an American, British and Irish citizen. They were later released. Also, a PA security forces HQ building was burnt down in Jenin by the al Aqsa Martyrs' Brigades. A leader of Al Aqsa Martyrs Brigades said they torched the building because new mayor Qadorrah Moussa, appointed by Arafat, had refused to pay salaries to Al Aqsa members or to cooperate with the group.[110]

On 8 August 2004 the Justice Minister Nahed Arreyes resigned stating that he has been stripped of much of his authority over the legal system. The year before, Yasser Arafat created a rival agency to the Justice Ministry and was accused of continuing to control the judiciary and in particular the state prosecutors.[111]

On 10 August 2004, a report by an investigation committee Palestinian Legislative Council for the reasons for the anarchy and chaos in the PA was published by Haaretz daily newspaper.[112] The report put the main blame on Yasser Arafat and the PA's security forces, which "have failed to make a clear political decision to end it". The report states,

- "The main reason for the failure of the Palestinian security forces and their lack of action in restoring law and order [......] is the total lack of a clear political decision and no definition of their roles, either for the long term or the short."

The report also calls to stop shooting Qassam rockets and mortar shells on Israeli settlements because it hurts "Palestinian interests". Hakham Balawi said:

- "... It is prohibited to launch rockets and to fire weapons from houses, and that is a supreme Palestinian interest that should not be violated because the result is barbaric retaliation by the occupying army and the citizenry cannot accept such shooting. Those who do it are a certain group that does not represent the people and nation, doing it without thinking about the general interest and public opinion in the world and in Israel. There is no vision or purpose to the missiles; the Palestinian interest is more important"[113]

Despite the criticism against Yasser Arafat, the troubles continued. On 24 August, the Lieutenant Commander of the Palestinian General Intelligence in the Gaza Strip, Tareq Abu-Rajab, was shot by group of armed men. He was seriously injured.[114]

On 31 August, the Jenin Martyrs Brigades, the armed wing of the Popular Resistance Committees, threaten to kill Minister Nabil Shaath for participating in a conference in Italy attended by Israeli Foreign Minister Silvan Shalom, declaring "He will be sentenced to death if he enters. The decision cannot be rescinded, we call upon his bodyguards to abandon his convoy in order to save their lives."[115]

On 8 September, Prime Minister Ahmed Qurei, threatens to resign, again. Three weeks have elapsed since he retracted is resignation, originally tendered six weeks ago.[116]

On 12 October, Moussa Arafat, cousin of Yasser Arafat and a top security official in the Gaza Strip, survived a car bomb assassination attempt. Recently[when?] the Popular Resistance Committees threatened Moussa Arafat with retaliation for an alleged attempt to assassinate its leader, Mohammed Nashabat.[117]

On 14 October, Palestinian Prime Minister Ahmed Qurei stated that the Palestinian Authority is unable to stop the spreading anarchy. While routinely blaming Israel for the PA's problems, he pointed out that the many PA security forces are hobbled by corruption and factional feuding. Due to the lack of governmental reforms demanded by international peace mediators, Palestinian legislators demanded Qurei present a report on the matter by 20 October, at which point they will decide upon holding a no-confidence vote.[118]

On 19 October, a group of Al-Aqsa Martyrs' Brigades members, led by Zakaria Zubeidi, seized buildings belonging to the Palestinian Finance ministry and Palestinian parliament in Jenin.[119]

According to Mosab Hassan Yousef, the CIA has provided sophisticated electronic eavesdropping equipment to the Palestinian Authority that has been used against suspected Palestinian militants. However, the equipment has also been used against Shin Bet informants.[120]

Palestinian measures to keep law and order

In 2006, after the Hamas victory, the Palestinian interior minister formed an Executive Force for the police. However, the PA president objected and after clashes between Hamas and Fatah, redeployment of the force was made and efforts started in order to integrate it with the police force.

In 2011, Amira Hass reported that in sections of Area B of the West Bank, especially around the towns of Abu Dis and Sawahera, a security paradox was evolving: while the Oslo Accords stipulate that the Israeli Army have authority to police Area B, they weren't; and though the Palestinian security forces were prepared to deal with criminal activity in this area, they had to wait for Israeli permission to enter, and were thus ineffective. Hass also reported that as a result of this paradox, Abu Dis and surrounding areas were becoming a haven for weapons smugglers, drug dealers, and other criminals.[121]

As of 2013, Palestinian security forces continue to coordinate with Israeli troops in tracking Islamic militants in the West Bank.[122]

Administrative divisions

The governorates (Arabic: محافظات muhafazat) of the Palestinian Authority were founded in 1995 to replace the 8 Israeli military districts of the Civil Administration: 11 governorates in the West Bank and 5 in the Gaza Strip. The governorates are not regulated in any official law of decree by the Palestinian Authority[123] but they are regulated by Presidential decrees, mainly Presidential Decree No. 22 of 2003, regarding the powers of the governors.[124]

The regional governors (Arabic: محافظ muhafiz) are appointed by the President. They are in charge of the Palestinian police force in their jurisdiction as well as coordinating state services such as education, health and transportation. The governorates are under the direct supervision of the Interior Ministry.[123]

The governorates in the West Bank are grouped into three areas per the Oslo II Accord. Area A forms 18% of the West Bank by area, and is administered by the Palestinian Authority.[125][126] Area B forms 22% of the West Bank, and is under Palestinian civil control, and joint Israeli-Palestinian security control.[125][126] Area C, except East Jerusalem, forms 60% of the West Bank, and is administered by the Israeli Civil Administration, except that the Palestinian Authority provides the education and medical services to the 150,000 Palestinians in the area.[125] 70.3% of Area C (40.5% of the West Bank) is off limit to Palestinian construction and development. These areas include areas under jurisdiction of Israeli settlements, closed military zones, nature reserves and national parks and areas designated by Israel as "state land".[127] There are about 330,000 Israelis living in settlements in Area C,[128] in the Israeli-occupied West Bank. Although Area C is under martial law, Israelis living there are judged in Israeli civil courts.[129]

| Name | Area[130] | Population | Density | muhfaza or district capital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jenin | 583 | 311,231 | 533.84 | Jenin |

| Tubas | 402 | 64,719 | 160.99 | Tubas |

| Tulkarm | 246 | 182,053 | 740.05 | Tulkarm |

| Nablus | 605 | 380,961 | 629.68 | Nablus |

| Qalqiliya | 166 | 110,800 | 667.46 | Qalqilya |

| Salfit | 204 | 70,727 | 346.7 | Salfit |

| Ramallah & Al-Bireh | 855 | 348,110 | 407.14 | Ramallah |

| Jericho & Al Aghwar | 593 | 52,154 | 87.94 | Jericho |

| Jerusalem | 345 | 419,108a | 1214.8a | Jerusalem (De Jure and disputed) |

| Bethlehem | 659 | 216,114 | 927.94 | Bethlehem |

| Hebron | 997 | 706,508 | 708.63 | Hebron |

| North Gaza | 61 | 362,772 | 5947.08 | Jabalya |

| Gaza | 74 | 625,824 | 8457.08 | Gaza City |

| Deir Al-Balah | 58 | 264,455 | 4559.56 | Deir al-Balah |

| Khan Yunis | 108 | 341,393 | 3161.04 | Khan Yunis |

| Rafah | 64 | 225,538 | 3524.03 | Rafah |

a. Data from Jerusalem includes occupied East Jerusalem with its Israeli population

East Jerusalem is administered as part of the Jerusalem District of Israel, but is claimed by Palestine as part of the Jerusalem Governorate. It was annexed by Israel in 1980,[125] but this annexation is not recognised by any other country.[131] Of the 456,000 people in East Jerusalem, roughly 60% are Palestinians and 40% are Israelis.[125][132]

Foreign relations

The Palestinian National Authority (PNA) foreign relations are conducted by the minister of foreign affairs. The PNA is represented abroad by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), which maintains a network of missions and embassies.[133] In states that recognise the State of Palestine it maintains embassies and in other states it maintains "delegations" or "missions".[134]

Representations of foreign states to the Palestinian Authority are performed by "missions" or "offices" in Ramallah and Gaza. States that recognise the State of Palestine also accredit to the PLO (as the government-in-exile of the State of Palestine) non-resident ambassadors residing in third countries.[135]

On 5 January 2013, following the 2012 UNGA resolution, Palestinian President Abbas ordered all Palestinian embassies to change any official reference to the Palestinian Authority into State of Palestine.[136][137]

The Palestinian Authority is included in the European Union's European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), which aims at bringing the EU and its neighbours closer.

Palestinian Authority passport

In April 1995, the Palestinian Authority, pursuant to the Oslo Accords with the State of Israel, started to issue passports to Palestinian residents of the Gaza Strip and West Bank. The appearance of the passport and details about its issuance are described in Appendix C of Annex II (Protocol Concerning Civil Affairs) of the Gaza-Jericho Agreement signed by Israel and the PLO on 4 May 1994. The Palestinian Authority does not issue the passports on behalf of the proclaimed State of Palestine.[138]: 231 The passports bear the inscription: "This passport/travel document is issued pursuant to the Palestinian Self Government Agreement according to Oslo Agreement signed in Washington on 13/9/1993".[139] By September 1995, the passport had been recognised by 29 states, some of them (e.g. the United States) recognise it only as a travel document (see further details below): Algeria, Bahrain, Bulgaria, People's Republic of China, Cyprus, Egypt, France, Germany, Greece, India, Iran, Jordan, Malta, Morocco, the Netherlands, Pakistan, Qatar, Romania, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Tunisia, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and the United States.[140]

While the U.S. Government recognises Palestinian Authority passports as travel documents, it does not view them as conferring citizenship, since they are not issued by a government that they recognise. Consular officials representing the Governments of Egypt, Jordan and the United Arab Emirates, when asked by the Resource Information Center of UNHCR in May 2002, would not comment on whether their governments viewed PA passports as conferring any proof of citizenship or residency, but did say that the passports, along with valid visas or other necessary papers, would allow their holders to travel to their countries.[141]

The Palestinian Authority has said that anyone born in Palestine carrying a birth certificate attesting to that can apply for a PA passport. Whether or not Palestinians born outside Palestine could apply was not clear to the PA Representative questioned by UNHCR representatives in May 2002. The PA representative also said even if those applying met the PA's eligibility criteria, the Israeli government placed additional restrictions on the actual issuance of passports.[141]

In October 2007, a Japanese Justice Ministry official said, "Given that the Palestinian Authority has improved itself to almost a full-fledged state and issues its own passports, we have decided to accept the Palestinian nationality." The decision followed a recommendation by a ruling party panel on nationality that Palestinians should no longer be treated as stateless.[142]

Legal action against PNA

In February 2015 in a civil case considered by a US federal court the Palestinian Authority and Palestine Liberation Organization were found liable for the death and injuries of US citizens in a number of terrorist attacks in Israel from 2001 to 2004. However, on 31 August 2016, the Second US Circuit Court of Appeals in Manhattan dismissed the lawsuit on the grounds that US federal courts lacked overseas jurisdiction on civil cases.[143][144][145]

Police forces

The creation of a Palestinian police force was called for under the Oslo Accords.[25] The first Palestinian police force of 9,000 was deployed in Jericho in 1994, and later in Gaza.[25] These forces initially struggled to control security in the areas in which it had partial controlled and because of this Israel delayed expansion of the area to be administered by the PA.[25] By 1996, the PA security forces were estimated to include anywhere from 40,000 to 80,000 recruits.[146] PA security forces employ some armored cars, and a limited number carry automatic weapons.[147] Some Palestinians opposed to or critical of the peace process perceive the Palestinian security forces to be little more than a proxy of the State of Israel.[25]

Economy

The Gaza International Airport was built by the PA in the city of Rafah, but operated for only a brief period before being destroyed by Israel following the outbreak of Al-Aqsa Intifada in 2000. A seaport was also being constructed in Gaza but was never completed.

Some Palestinians are dependent on access to the Israeli job market. During the 1990s, some Israeli companies began to replace Palestinians with foreign workers.[citation needed] The process was found to be economical and also addressed security concerns. This hurt the Palestinian economy, in particular in the Gaza strip, where 45.7% of the population is under the poverty line according to the CIA World Factbook, but it also affected the West Bank.

Budget

According to the World Bank, the budget deficit in PNA was about $800 million in 2005, with nearly half of it financed by donors. The World Bank stated, "The PA's fiscal situation has become increasingly unsustainable mainly as a result of uncontrolled government consumption, in particular a rapidly increasing public sector wage bill, expanding social transfer schemes and rising net lending."[148]

In June 2011, Prime Minister Salam Fayyad stated that the Palestinian Authority is facing a financial crisis because funds pledged by donor nations have not arrived on time. Fayyad said that "In 2011, we have been receiving $52.5 million dollars a month from the Arab countries, which is much less than the amount they committed to deliver."[149]

In June 2012, the Palestinian Authority was unable to pay its workers' salaries as a result of their financial issues, including a cutback in aid from foreign donors, and Arab countries not fulfilling their pledges to send money to the Palestinian Authority, in which the Palestinian Authority is heavily dependent. Finance Minister Nabil Kassis called the crisis "the worst" in three years.[150][151][152][153] Adding to the complications are the fact that in the same month, the head of the Palestine Monetary Authority, Jihad Al-Wazir, stated that the Palestinian Authority reached the maximum limit of borrowing from Palestinian banks.[154]

In July 2012, Prime Minister Salam Fayyad urged Arab countries to send the money they promised, which amounts to tens of millions of dollars, as they have not made good on their pledges, while Western donors have.[155] The Palestinian labor minister Ahmed Majdalani also warned of the consequences of a shortfall in the delivery of aid from Arab donor nations.[156]

In order to help the Palestinian Authority solve its crisis, Israel sought $1 billion in loans from the International Monetary Fund, intending to transfer this loan to the Palestinian Authority who would pay them back when possible. The IMF rejected the proposal because it feared setting a precedent of making IMF money available to non-state entities, like the Palestinian Authority, which as a non-state cannot directly request or receive IMF funding.[157][158][159][160]

In mid-July 2012, it was announced that Saudi Arabia would imminently send $100 million to the Palestinian Authority to help relieve them of their financial crisis. Still, the Palestinian Authority is seeking the support of other countries to send more money to help fix a budget deficit that is approximately $1.5 billion for 2012, and it is estimated that they need approximately $500 million more. Ghassan Khatib, a Palestinian Authority spokesman, said, "This $100 million is important and significant because it's coming from a leading Arab state, and this hopefully can be an example for other countries to follow... We will remain in need of external funding. Whenever it is affected, then we will be in crisis."[161][162]

By 15 July 2012, Palestinian Authority workers received only 60% of their salaries for June, which caused discontent against the government.[162]

In a "goodwill gesture" to the Palestinian Authority to renew dialogue with Israel, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Finance Minister Yuval Steinitz decided to give Ramallah a NIS 180 million advance on tax money it transfers on a monthly basis. The Israeli government's economic cabinet also decided to increase the number of Palestinian construction workers allowed in Israel by approximately 5,000. One Israeli official said that the money helped the Palestinian Authority pay its salaries before Ramadan, and it was part of Israel's policy of helping to "preserve the Palestinian economy."[163]

The World Bank issued a report in July 2012 that the Palestinian economy cannot sustain statehood as long as it continues to heavily rely on foreign donations and the private sector fails to thrive. The report said that the Palestinian Authority is unlikely to reach fiscal sustainability until a peace deal is achieved that allows the private sector to experience rapid and sustained growth. The World Bank report also blamed the financial issues on the absence of a final status agreement that would allow for a two-state solution to the Israeli-Arab conflict.[164]

As of May 2011, the Palestinian Authority spent $4.5 million per month paying Palestinian prisoners. The payments include monthly amounts such as NIS 12,000 ($3,000) to prisoners who have been imprisoned for over 30 years. The salaries, funded by the PA, are given to Fatah, Hamas, and Islamic Jihad prisoners, despite financial hardships by the Palestinian Authority. These payments make up 6% of the PA's budget.[165]

As of January 2015[update], the PA has a debt of 1.8 bln NIS to the Israel Electric Corporation.[166]

In 2017, the PA received $693 million from foreign donors, of which $345 million, was paid out through the Martyrs Fund in the form of stipends to convicted militants and their families.[167]

Corruption

A poll conducted by the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research revealed that 71% of Palestinians believe there is corruption in the Palestinian Authority institutions in the West Bank, and 57% say there is corruption in the institutions of the dismissed Palestinian government in the Gaza Strip. 34% say that there is no freedom of the press in the West Bank, 21% say that there is press freedom in the West Bank, and 41% say there is to a certain extent. 29% of Palestinians say people in the West Bank can criticize the government in the West Bank without fear.[168][169][170]

At a hearing of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs in the United States Congress on 10 July 2012, titled "Chronic Kleptocracy: Corruption within the Palestinian Political Establishment," it was stated that there is serious corruption within the political establishment and in financial transactions.[171] The experts, analysts, and specialists testified on corruption within financial transactions concerning Mahmoud Abbas, his sons Yasser and Tareq, and the Palestine Investment Fund, among others, as well as on the limiting of freedom of the press, crushing political opposition, and cracking down on protestors. According to Representative Steve Chabot, who testified at the hearing, "Reports suggest that Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas, like his predecessor Yassir Arafat, has used his position of power to line his own pockets as well as those of his cohort of cronies, including his sons, Yasser and Tareq. The Palestinian Investment Fund, for example, was intended to serve the interests of the Palestinian population and was supposed to be transparent, accountable, and independent of the Palestinian political leadership. Instead, it is surrounded by allegations of favoritism and fraud." Concerning Abbas' children, Chabot stated that "Even more disturbingly, Yasser and Tareq Abbas—who have amassed a great deal of wealth and economic power—have enriched themselves with U.S. taxpayer money. They have allegedly received hundreds of thousands of dollars in USAID contracts."[172][173]

In April 2013, the Palestinian organization Coalition for Transparency in Palestine said it was investigating 29 claims of stolen public funds. In addition, they said that the PA "has problems with money laundering, nepotism and misusing official positions." Twelve earlier claims were investigated and sent to the courts for resolution. In response, Palestinian Authority Justice Minister Ali Muhanna said that they have "made large strides in reducing corruption."[174]

International aid

The majority of aid to the Palestinian Authority comes from the United States and European Union. According to figures released by the PA, only 22 percent of the $530,000,000 received since the beginning of 2010 came from Arab donors. The remaining came from Western donors and organizations. The total amount of foreign aid received directly by the PA was $1.4 billion in 2009 and $1.8 billion in 2008.[175]

Palestinian leaders stated the Arab world was "continuing to ignore" repeated requests for help.[176]

The US and the EU responded to Hamas' political victory by stopping direct aid to the PA, while the US imposed a financial blockade on PA's banks, impeding some of the Arab League's funds (e.g. Saudi Arabia and Qatar) from being transferred to the PA.[177] On 6 and 7 May 2006, hundreds of Palestinians demonstrated in Gaza and the West Bank demanding payment of their wages.

In 2013 there are 150,000 government employees. Income to run the government to serve about 4 million citizens, comes from donations from other countries.[178]

In 2020, Swedish foreign aid minister Peter Eriksson (Green Party) announced a 1.5 billion SEK support package (about 150 million euro) to the Palestine Authority in 2020–2024. This announcement came after several other countries had reduced aid due to indicators of corruption and that funds go towards the salaries of militants.[179]

Economic sanctions following January 2006 legislative elections

Following the January 2006 legislative elections, won by Hamas, the Quartet (the United States, Russia, the European Union, and the United Nations) threatened to cut funds to the Palestinian Authority. On 2 February 2006, according to the AFP, the PA accused Israel of "practicing collective punishment after it snubbed the US calls to unblock funds owed to the Palestinians." Prime minister Ahmed Qorei "said he was hopeful of finding alternative funding to meet the budget shortfall of around 50 million dollars, needed to pay the wages of public sector workers, and which should have been handed over by Israel on the first of the month." The US Department criticized Israel for refusing to quickly unblock the funds. The funds were later unblocked.[180] However, the New York Times alleged on 14 February 2006 that a "destabilization plan" of the United States and Israel, aimed against Hamas, winner of the January 2006 legislative elections, centered "largely on money" and cutting all funds to the PA once Hamas takes power, in order to delegitimize it in the eyes of the Palestinians. According to the news article, "The Palestinian Authority has a monthly cash deficit of some $60 million to $70 million after it receives between $50 million and $55 million a month from Israel in taxes and customs duties collected by Israeli officials at the borders but owed to the Palestinians." Beginning March 2006, "the Palestinian Authority will face a cash deficit of at least $110 million a month, or more than $1 billion a year, which it needs to pay full salaries to its 140,000 employees, who are the breadwinners for at least one-third of the Palestinian population. The employment figure includes some 58,000 members of the security forces, most of which are affiliated with the defeated Fatah movement." Since 25 January elections, "the Palestinian stock market has already fallen about 20 percent", while the "Authority has exhausted its borrowing capacity with local banks."[181]

Use of European Union assistance

In February 2004, it was reported that the European Union (EU) anti-fraud office (OLAF) was studying documents suggesting that Yasser Arafat and the Palestinian Authority had diverted tens of millions of dollars in EU funds to organizations involved in terrorist attacks, such as the Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades. However, in August 2004, a provisional assessment stated that "To date, there is no evidence that funds from the non-targeted EU Direct Budget Assistance to the Palestinian Authority have been used to finance illegal activities, including terrorism."[182]

US foreign aid packages

The US House for Foreign Operations announced a foreign assistance package to the Palestinian Authority that included provisions that would bar the government from receiving aid if it seeks statehood at the UN or includes Hamas in a unity government. The bill would provide $513 million for the Palestinian Authority.[183]

Payments to Palestinian prisoners in Israeli prisons

On 22 July 2004, Salam Fayyad, PA Minister of Finance, in an article in the Palestinian weekly, The Jerusalem Times, detailed the following payments to Palestinians imprisoned by the Israeli authorities:[184]

- Prisoner allowances increased between June 2002 and June 2004 to $9.6M USD monthly, an increase of 246 percent compared with January 1995 – June 2002.

- Between June 2002 and June 2004, 77M NIS were delivered to Palestinians held in Israeli prisons, compared to 121M NIS between January 1995 and June 2002, which is an increase of 16M NIS yearly. The increase of annual spending between the two periods registers 450 percent, which is much higher than the percentage increase of the number of prisoners.

- Between 2002 and 2004, the PA paid 22M NIS to cover other expenses – lawyers' fees, fines, and allocations for released prisoners. This includes lawyers' fees paid directly by the PA and fees paid through the Prisoners Club.

In February 2011, The Jerusalem Post revealed that the PA was paying monthly salaries to members of Hamas who are in Israeli prisons.[185]

In March 2009, an extra 800 shekels ($190) was added to the stipends given to Palestinians affiliated with PLO factions in Israeli prisons, as confirmed by the head of Palestinian Prisoner Society in Nablus Ra'ed Amer. Each PLO-affiliated prisoner receives 1,000 shekels ($238) per month, an extra 300 shekels ($71) if they are married, and an extra 50 shekels ($12) for each child.[186]

In 2016 the United Kingdom had a domestic debate about how its aid to the PA ended up funding prisoners incarcerated in Israel.[187] In October 2016 a sum of £25 million, constituting a third of its aid payments, was withheld pending the results of an investigation.[citation needed]

James G. Lindsay

James G. Lindsay a former UNRWA general-counsel and fellow researcher for Washington Institute for Near East Policy published a report regarding the use of international aid in the Palestinian Authority. Lindsay argued that internationally funded construction projects in the West Bank should try to minimize foreign labor and maximize the participation of Palestinian workers and management to ensure economic expansion through salaries, job training, and improved infrastructure. Lindsay stated that some financial control should stay in international hands to avoid "nepotism or corruption".[188]

Lindsay has also argued that in any peace settlement acceptable to Israel "there will be few, if any, Palestinian refugees returning to Israel proper".[188] Lindsay suggested that internationally funded construction projects should try to benefit West Bank refugees who are willing to give up their longstanding demand for a "right of return". Lindsay also claimed that projects that will improve the living conditions of West Bank refugees could also be seen as part of the reparations or damages to be paid to refugees in any likely Israeli-Palestinian agreement. Lindsay criticized the Palestinian Authority treatment of these refugees:

PA projects are not likely to address refugee needs, however, since the PA has traditionally deferred to the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) regarding infrastructure in refugee camps.[188]

See also

Notes and references

- ^ "Palestine" (includes audio). nationalanthems.info. Archived from the original on 31 March 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ^ a b Thrall 2017, p. 144: the West Bank was divided into 165 islands of ostensible PA control; Peteet 2016, p. 268: In total, over 167 enclaves can be identified

- ^ "The Palestinian Authority". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- ^ "Article IV: Monetary and Financial Issues", Gaza-Jericho Agreement Annex IV - Economic Protocol, Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 29 April 1994, archived from the original on 7 August 2004, retrieved 20 February 2023The Protocol allows the Palestinian Authority to adopt multiple currencies. In the West Bank, the Israeli new sheqel and Jordanian dinar are widely accepted; while in the Gaza Strip, the Israeli new sheqel and Egyptian pound are widely accepted.

- ^ "The World Factbook: Middle East: Gaza Strip". cia.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. 12 May 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ^ a b c "Palestine: What is in a name (change)?". Inside Story. Al Jazeera. 8 January 2013. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- ^ a b Rudoren, Jodi. "The Palestinian Authority". The New York Times.

- ^ a b "The Palestinian government". CNN. 5 April 2001. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- ^ "Status of Palestine in the UN - Non-member observer State status - SecGen report". Question of Palestine. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ Kumaraswamy, P. R. (2009). The A to Z of the Arab-Israeli Conflict. The A to Z Guide Series. Vol. 66. Scarecrow Press. p. xl. ISBN 978-0-8108-7015-4.

- ^ "Israel completes Gaza withdrawal". BBC News. 12 September 2005. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ "US suspends aid to Palestinians", BBC News, 7 April 2006, retrieved 7 April 2006

- ^ "Abbas warns of financial crisis", BBC News, 20 February 2006, retrieved 19 February 2006

- ^ Akiva Eldar, "U.S. to allow PA funds to be channeled through Abbas office", Haaretz

- ^ Patrick Martin (18 July 2009), "Fancy that, a moderate in Hamas", The Globe and Mail, Toronto, archived from the original on 23 August 2009, retrieved 3 August 2009

- ^ Hamas Says Dweik 'Real President' until Elections are Held, Al-Manar, 25 June 2006, retrieved 3 August 2009[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Gharib, Ali (20 December 2012). "U.N. Adds New Name: "State of Palestine"". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 1 January 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ a b "Permanent Observer Mission of Palestine to the United Nations". United Nations. Archived from the original on 31 January 2013. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

**Please note that since Thursday's Historic Vote in the United Nations General Assembly which accorded to Palestine Observer State Status, the official title of the Palestine mission has been changed to The Permanent Observer Mission of the State of Palestine to the United Nations.**

- ^ "A/67/L.28 of 26 November 2012 and A/RES/67/19 of 29 November 2012". United Nations. Archived from the original on 10 December 2012. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- Rahman, Omar H. (2 July 2021). "U.S. Support Is Keeping the Undemocratic Palestinian Authority Alive". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- Oppenheim, Beth. "Halting Palestine's Democratic Decline". Carnegie Europe. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- "Two Authorities, One Way, Zero Dissent: Arbitrary Arrest and Torture Under the Palestinian Authority and Hamas". Human Rights Watch. 23 October 2018.

- El Kurd, Dana (2020). Polarized and Demobilized: Legacies of Authoritarianism in Palestine. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190095864.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-009586-4.

- Hugh Lovatt; Saleh Hijazi (20 April 2017). "Europe and the Palestinian Authority's Authoritarian Drift – European Council on Foreign Relations". ECFR. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- Kershner, Isabel; Rasgon, Adam (7 July 2021). "Critic's Death Puts Focus on Palestinian Authority's Authoritarianism". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- "West Bank: Freedom in the World 2021 Country Report". Freedom House. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ Oslo Accords, Article I

- ^ Oslo Accords, Article V

- ^ Gaza–Jericho Agreement, Article XXIII, Section 3

- ^ a b c d Pages 44–49 of the written statement submitted by Palestine Archived 5 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine, 29 January 2004, in the International Court of Justice Advisory Proceedings Archived 6 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine on the Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory Archived 30 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine, referred to the court Archived 5 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine by U.N. General Assembly resolution A/RES/ES-10/14 (A/ES-10/L.16) adopted on 8 December 2003 at the 23rd Meeting of the Resumed Tenth Emergency Special Session.

- ^ a b c d e Eur 2003, p. 521

- ^ Rothstein 1999, p. 63

- ^ Brown 2003, p. 49

- ^ Watson 2000, p. 62

- ^ "Mediators tell Palestinians to reform or lose aid", China Daily, archived from the original on 10 February 2006, retrieved 19 February 2006

- ^ "Bataille pour le trésor de l'OLP", Le Figaro, archived from the original on 9 November 2004, retrieved 6 February 2005

- ^ The Basic Law, miftah.org, archived from the original on 19 June 2006, retrieved 29 May 2006

- ^ Putin offers to help Palestinians, BBC, 29 April 2005, retrieved 19 February 2006

- ^ CRS Report for Congress, 27 June 2006, U.S. Foreign Aid to the Palestinians Archived 26 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Palestinian prime minister vows not to recognize Israel", USA Today, Associated Press, 8 December 2006, retrieved 21 May 2010

- ^ "Mubarak Calls Hamas' Takeover of the Gaza Strip a 'Coup'". Haaretz. Israel. Associated Press. 4 May 2012. Archived from the original on 25 June 2007.

- ^ Miller, Elhanan. "Prisoner protests mark PA effort to start a 'popular intifada'". The Times of Israel.

- ^ Jacobs, Phil (30 December 2008), "Tipping Point After years of rocket attacks, Israel finally says, 'Enough!'", Baltimore Jewish Times, archived from the original on 15 January 2009, retrieved 7 January 2009

- ^ New York Times (18 June 2008), "Israel Agrees to Truce with Hamas on Gaza", The New York Times, archived from the original on 17 April 2009, retrieved 28 December 2008

- ^ "TIMELINE – Israeli-Hamas violence since truce ended", Reuters, 5 January 2009

- ^ McCarthy, Rory (5 November 2008). "Gaza truce broken as Israeli raid kills six Hamas gunmen". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 6 January 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- ^ McGreal, Chris (4 January 2009). "Why Israel went to war in Gaza". The Observer. The Guardian. ISSN 0029-7712. Archived from the original on 22 September 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- ^ "Hamas declares Israel truce over", BBC News, 22 December 2008, retrieved 3 January 2010

- ^ Harel, Amos (27 December 2008), ANALYSIS / IAF strike on Gaza is Israel's version of 'shock and awe', Ha’aretz, archived from the original on 25 August 2009, retrieved 27 December 2008

- ^ a b c "Rival Fatah, Hamas movements reach unity deal". CNN. 27 April 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ a b "Fatah, Hamas agree general elections". The Voice of Russia. 27 April 2011. Archived from the original on 20 September 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ Levy, Elior; Somfalvi, Attila (27 April 2011). "Fatah, Hamas sign reconciliation agreement". Ynetnews. Israel News; Yedioth Internet. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ a b "Palestinian PM unveils measures to calm protests". BBC. 11 September 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- ^ "Report of possible Gaza independence stirs debate". Al Arabiya. 31 July 2012. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- ^ Beaumont, Peter; Lewis, Paul (24 April 2014). "Fatah and Hamas agree landmark pact after seven-year rift". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ "Fatah, Hamas agree to form Palestinian unity government". France 24. 23 April 2014. Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ "International community welcomes Palestinian unity government". The Jerusalem Post. 6 March 2014. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- ^ Panda, Ankit (4 June 2014). "India and China Back Unified Palestinian Government". thediplomat.com. Archived from the original on 14 March 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- ^ Wroughton, Lesley; Zengerle, Patricia (2 June 2014). "Obama administration to work with Palestinian unity government". Reuters. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- ^ "Amid wave of endorsements, PM 'troubled' by U.S. decision to work with Palestinian gov't". Haaretz. 3 June 2014.

- ^ "Palestinian unity government sworn in by Mahmoud Abbas". BBC News. BBC. 2 June 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ Rudoren, Jodi; Kershner, Isabel (2 June 2014). "With Hope for Unity, Abbas Swears in a New Palestinian Government". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ Ariel Ben Solomon (30 November 2014). "Hamas says unity government is over". The Jerusalem Post.

- ^ "Hamas: Palestinian unity govt has expired". MA’AN NEWS AGENCY. 30 November 2014. Archived from the original on 30 January 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ^ Lazar Berman (1 December 2014). "Fatah official denies unity government mandate has ended". The Times of Israel.

- ^ Abou Jalal, Rasha (8 March 2016). "Why does Hamas, Fatah reconciliation keep failing? the foreign pressures on the Palestinian Authority to not implement the reconciliation terms". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2016.